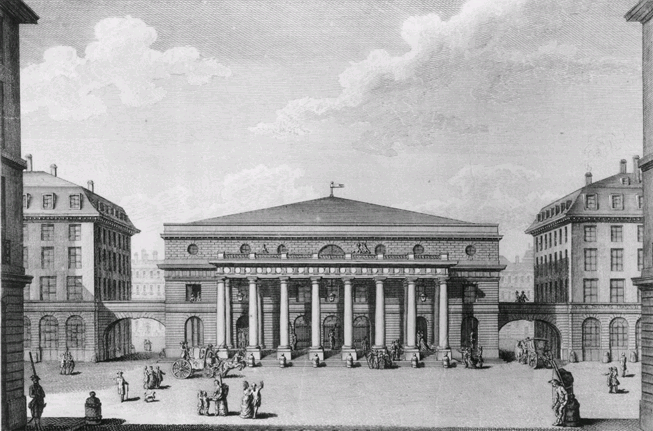

Théâtre de l'Odéon

Photo: Wikimedia, 2009

Théâtre de l'Odéon during the Revolution

Jean-Marc Nattier (1685–1766)

Portrait of Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais, 1755

London, private collection

The hôtel Amelot de Bisseuil, also known as Hôtel des Ambassadeurs de Hollande, in Paris

Photo: Ralf Treinen, 2009, Wikimedia

Beaumarchais at the Odéon

The word comédien(ne) in French does not mean "comedian" (comique means "comedian"). It simply means "actor," and thus Comédie Française designates a theater where plays in general take place, not merely "comedies." The theater now called the Odéon-Théâtre de l'Europe stands on the site of the original Comédie Française. Established in 1782, the theater was destroyed by fire in 1799, after which the company moved to its current Right Bank home by the Palais-Royal. The building before you is the oldest theater in Paris, dating from 1819, and at one time was the biggest, with 1,913 seats.

The original theater on this spot is where The Marriage of Figaro by Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais, who lived nearby, premiered on April 27, 1784. It was deemed a revolutionary play and the king's agents almost imprisoned Beaumarchais for it.

Beaumarchais was perhaps the most colorful of the French patriots to aid in the American revolutionary cause. His plays The Barber of Seville and The Marriage of Figaro secured his place in history, but his secret activity as gunrunner for the colonies made him one of the unsung heroes of the Revolution.

Pierre-Auguste Caron, son of a clockmaker, developed a mechanism for pocket watches that won him the post of official clockmaker to Louis XV. At court, he met his first wife, a wealthy widow. It was her land that allowed him to add “de Beaumarchais” to his name.

In the 1770s, as a spy at the English court for Louis XVI, he met influential colonists such as Arthur Lee, a wealthy Virginian, who sparked Beaumarchais’s interest in the fledgling rebellion. A liberal thinker, Pierre was easily swayed to the cause and he in turn persuaded Louis XVI's foreign minister, Charles Gravier, Comte de Vergennes, to aid the rebels. To allow France to preserve the appearance of neutrality, Beaumarchais set up a trading company as a front. France secretly gave it a million livres in May 1776.

Beaumarchais oversaw the shipment of 25,000 pounds of ammunition, plus guns and uniforms, to the colonies, working through Silas Deane, who, you may recall, was the first American expat. These supplies helped the Americans win the battle of Saratoga in 1777, after which France openly gave military and naval support.

Even while thus engaged, Beaumarchais found time to write The Marriage of Figaro, which Thomas Jefferson, an enthusiastic theatergoer, saw here on August 4, 1786. At that time this was the new home of the Comédie-Française, now near the Palais-Royal.

Beaumarchais did not flourish under his own country’s revolution: after a period in exile, he spent his final years in Paris in relative poverty and died in 1799. Part of his misfortune was also due to a certain stinginess on the part of his American "friends," who did not see fit to pay for the arms and clothes he had supplied to their army, under the pretext that they had been paid for by their French allies. Arthur Lee, a bitter enemy of Beaumarchais, was among those who convinced Congress to not pay the playwright a dime. It was not until 57 years later, after many unsuccessful attempts, that the American government finally recognized its debt - but paid no more than one-seventh of what was due.