Photo: Milton Alan Turner (2006)

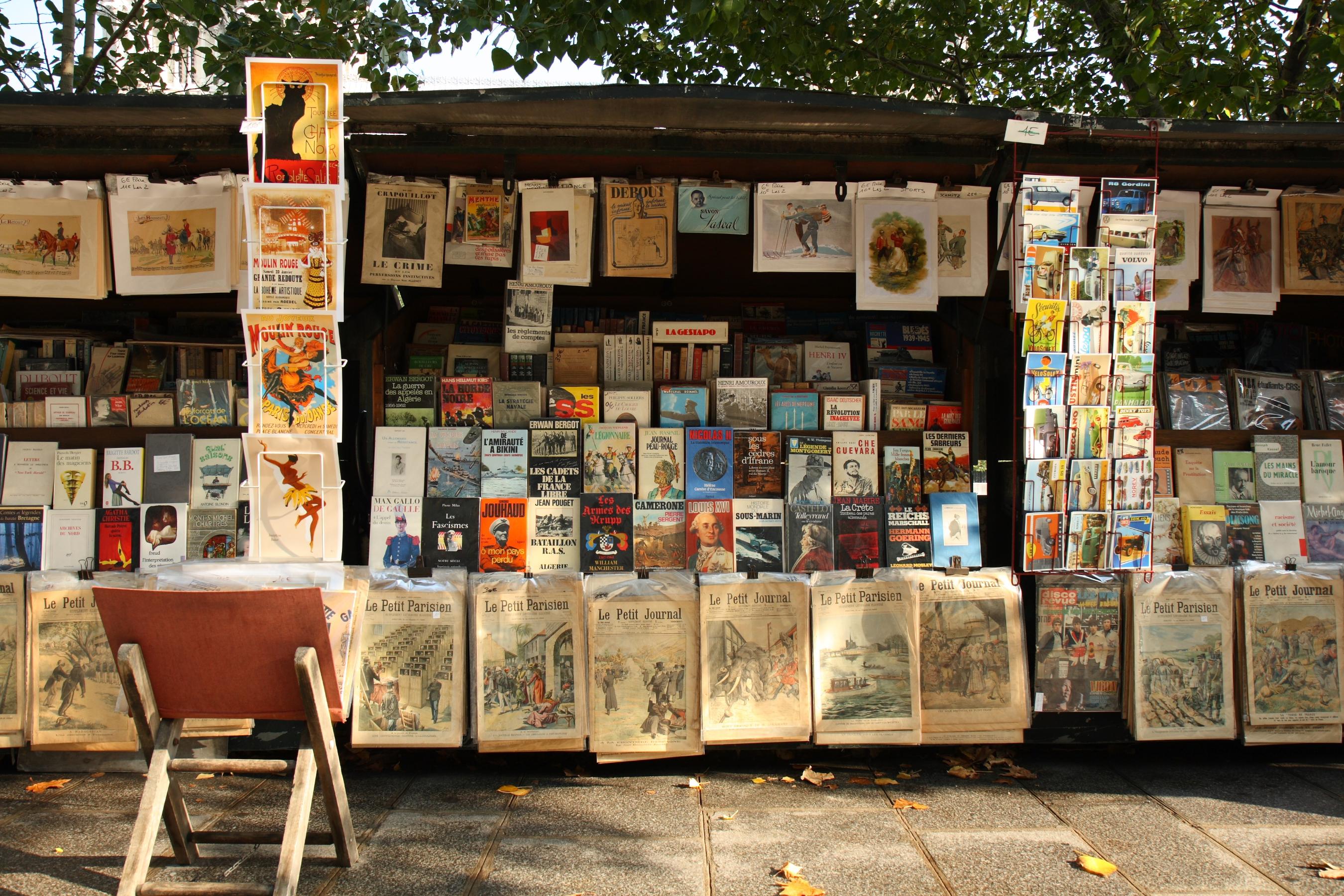

Photo: Benh Lieu Song (2007)

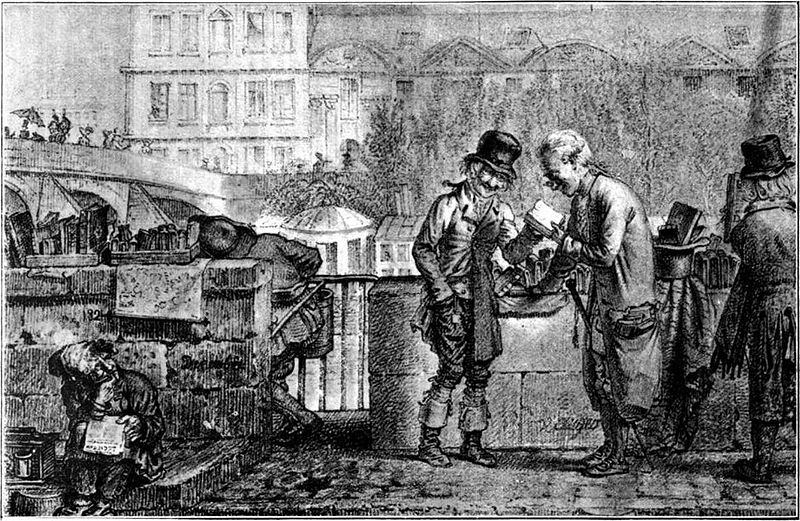

Jean Henry Marlet after Adrien Victor Auger

Secondhand Bookseller on the Quai Voltaire in Paris France, 1821

Source Charles Simond, La vie parisienne à travers le XIXe siècle, Paris, E. Plon, Nourrit et cie, 1900, p. 458

Decorating the House

Originally an extension of Quai Malaquais, Quai Voltaire was renamed in 1791 for Francois-Marie Arouet, whose nom de plume (pen name) was Voltaire. At number 27 you'll see a plaque indicating that on May 30, 1778, the great philosopher died in this house, which belonged to his protégé and fellow Freemason the Marquis de Villette. (After Voltaire's death, his niece/housekeeper, Marie Louise Denis, gave his embalmed heart to the marquis and his wife, who kept it in a silver case. It was the custom well into the 19th century to remove the hearts of illustrious men for preservation after their death.)

As we said in the introduction, whereas Ben Franklin "built" the house that was to become the United States, Jefferson "decorated" it. One of his most significant yet least known contributions was his sowing the seeds of the Library of Congress. The original library, located in the Capitol, was small and contained only legal tomes and other "books as may be necessary for the use of Congress," in the words of the legislation that created it in 1800. When invading British troops set fire to the Capitol in August 1814, the library was destroyed. A month later, retired president Thomas Jefferson, who had spent 50 years amassing books–"putting by," as he wrote, "everything which related to America, and indeed whatever was rare and valuable in every science"–sold his approximately 6,500 volumes to Congress, which had appropriated $23,950 for the purchase. So, what does this have to do with today's tour? Look to your left, as far as the eye can see. It was at these bouquiniste stalls, which for centuries have been a fixture along the Seine, that Jefferson purchased some of his most prized books, and thus some of the most interesting and valuable to be found in the Library of Congress today. At the time, some officials were surprised or bothered by the fact that this acquisition included works not necessary or even appropriate for a legislative library, such as books on science/philosophy, works of literature and books in foreign languages. To such critics Jefferson wrote, "I do not know that it contains any branch of science which Congress would wish to exclude from their collection; there is, in fact, no subject to which a Member of Congress may not have occasion to refer." This Jeffersonian concept of universality remains the basis of the Library of Congress's policy of all-inclusive collecting.