Laurent Dabos (died 1835)

Portrait of Thomas Paine, 1791

London, National Portrait Gallery

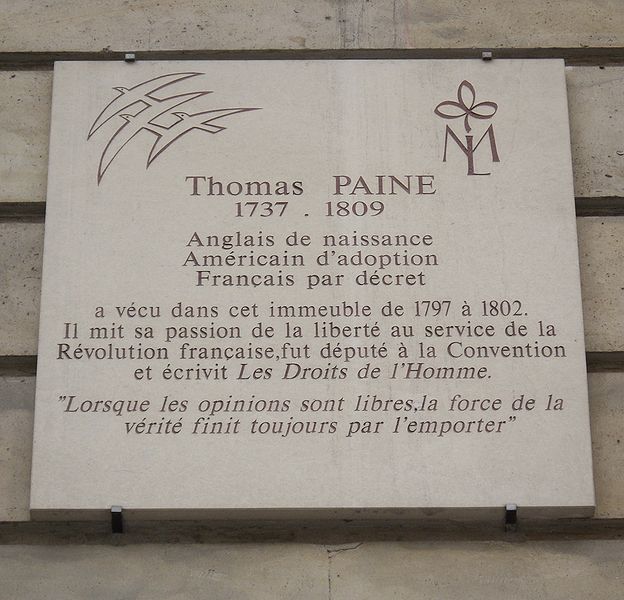

Plaque dedicated to Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine

1737-1809

Anglais de naissance

Américain d'adoption

Français par décret

a vécu dans cet immeuble de 1797 à 1802. Il mit sa passion de la liberté au service de la Révolution française, fut député à la Convention et écrivit Les Droits de l'Homme.

« Lorsque les opinions sont libres, la force de la vérité finit toujours par l'emporter. »

Photo: Wikimedia/MU, 2010

Thomas Paine on Rue de l'Odéon

The street, opened in 1779, was initially called Rue du Théâtre Français (you can see the theater, now the Théâtre de l'Odéon, at the top of the incline). Rue de l'Odéon was the first Paris street with sidewalks and side gutters. It was important to the Lost Generation (Hemingway, Fitzgerald, etc.) as the location of Shakespeare and Company, the bookshop owned by Sylvia Beach, who, as the plaque at number 12 states, published James Joyce's Ulysses. Today's Shakespeare and Company across from Notre Dame, celebrated as it is, has nothing to do with this one. For its literary aura, Joyce nicknamed this street Stratford-on-Odéon.

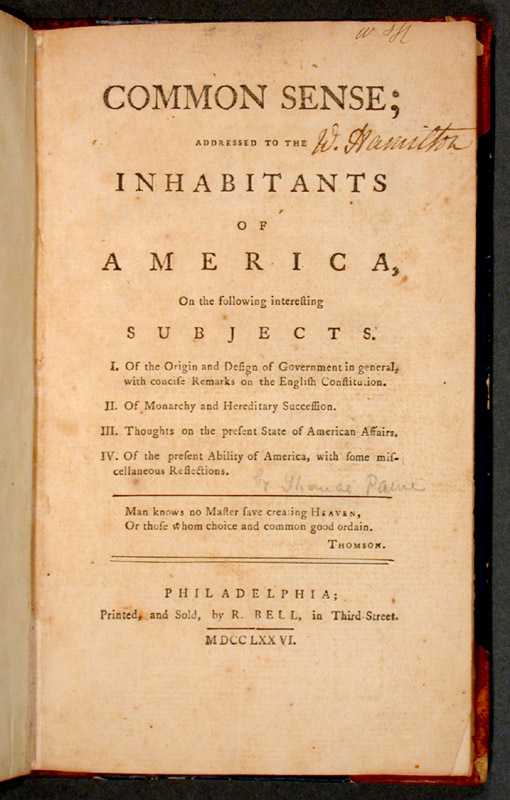

We're here, though, for Thomas Paine: "English by birth, American by adoption, French by decree", to quote the plaque at number 10, home of his printer and friend, Nicholas Bonneville, where Paine lived from 1797 (at the age of 60) until his return to the U.S. in 1802. Paine came to France in the early 1790s to seek food, clothing, ammunition and money for the U.S. Army. While he is certainly recognized as a U.S. Founding Father, his influence on both sides of the Atlantic seems to have been even greater than his renown suggests. John Adams said, "History will ascribe the American Revolution to Thomas Paine" and "Without the pen of the author of Common Sense, the sword of Washington would have been raised in vain." Danton told Paine, "What you have done for the happiness and liberty of your country, I have in vain tried to do for mine." France acclaimed him as a symbol of freedom; after the American Revolution he attempted to establish republics in France and in England. And although he could not speak the language, Thomas Paine was elected to the French National Assembly in 1792 (thus the "French by decree" part of the plaque). He even went Benjamin Franklin one better: When the elder statesman said, "Where liberty is, there is my country," the younger political author, activist and theorist responded, "Where liberty is not, there is mine."

Thomas Paine

Original cover of the "Common Sense"

But because Paine voted against the execution of Louis XVI, he found himself on the wrong side of Robespierre, who had him jailed in one of the makeshift prisons set up during the Reign of Terror to accommodate the numerous perceived enemies of the Revolution. That makeshift prison, right behind the theater you see at the end of Rue de l'Odéon (to your left, if you're facing the Paine plaque), was the Palais de Luxembourg, originally built for Marie de Médicis, now the seat of France's Senate. Paine's life was saved by the stupidity of a prison guard: an "X" was to be marked on the door of each inmate slated for execution, but a doctor, in Paine's cell to treat him for a fever, had left the door open, so the guard put the fatal mark on the inside of the door where it would be out of sight as soon as the door was closed!