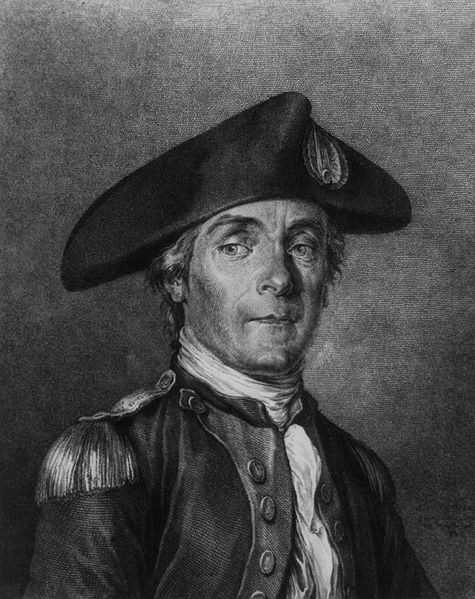

Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827)

John Paul Jones, 1781-1784

Jones wears the French Cross of the Institution of Military Merit (the gold medal hanging from a blue ribbon through the top left buttonhole). Louis XVI presented this medal to him in 1780.

Independence National History Park

Moreau le Jeune

American Revolutionary War hero John Paul Jones (1747-1792)

Portrait drawn from life and engraved (etching) in 1780, completed by Jean-Baptiste Fossoyeux (burin) in 1781.

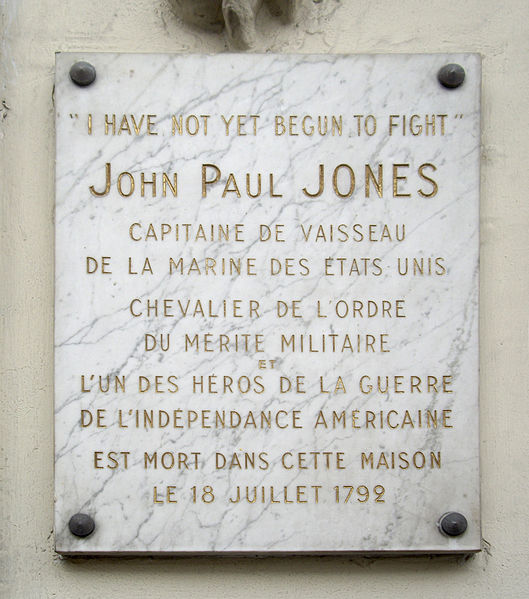

Two Foreigners in Service to America

The plaque here notes that John Paul Jones died in this building (in bed in his third-floor apartment) on July 18, 1792. A Scotsman who began his naval career as an apprentice at the age of 13, Jones first came to Paris in 1778 to advise the American commissioners, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams and Arthur Lee, on how American naval strategy could advance the colonists' cause with the French. (Like Franklin, he also advanced his own cause with the ladies of the French court.) He wound up earning recognition as the foremost naval hero of the American Revolution and the "Father of the American Navy."

After the French treaty of alliance with America was signed on February 6, 1778, Jones's ship, the USS Ranger, received the first salute to a U.S. vessel by the French navy, a 9-gun salvo. In September 1779 he commanded the USS Bonhomme Richard–named for his friend Ben Franklin's Poor Richard's Almanack (bonhomme roughly means "chap"). This was a merchant ship rebuilt and given to America by a French shipping magnate. With this ungainly vessel, he captured the British frigate HMS Serapis in a battle at very close quarters on September 23, 1779, off the coast of Yorkshire. Jones's ensign, the new Stars and Stripes, had been shot away, so the captain of the Serapis demanded if he had struck his colors in surrender. "Struck, sir?" Jones yelled. "I have not yet begun to fight!" Though he won the battle, his ship was so badly damaged that it sank, so he sailed the Serapis back to France, where he was knighted by Louis XVI and invited to the opera by Marie Antoinette.

Engraving from Richard Paton (1717–1791)

Action Between the Serapis and Bonhomme Richard, 1780

Buried in the St-Louis Cemetery for Foreign Protestants in Paris's 10th arrondissement (near today's Canal St-Martin), John Paul Jones was all but forgotten for more than a century. In 1905, the U.S. ambassador to France, General Horace Porter, identified Jones's remains after a search that lasted six years (partly due to faulty copies of the burial record). Fortunately, a royal commissioner who had greatly admired Jones had paid for a lead coffin filled with alcohol to preserve Jones's body. Ambassador Porter and a team of historians, researchers and an anthropologist located the cemetery, by then paved over, and used probes to search for lead coffins. The third one, unearthed on April 7, 1905, contained Jones's well preserved body. The formal identification was made at the Ecole de Médecine by U.S. and French experts, with additional confirmation resulting from a comparison of the face with a bust sculpted by Jean-Antoine Houdon. John Paul Jones was given a proper memorial service at the American Cathedral of Paris before being transported to the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland, where his final resting place is a national shrine.

The area where the tomb of John Paul Jones was found

The spot where his body was unearthed

The tomb of John Paul Jones in Annapolis

Look directly across Rue de Tournon. At number 10, you'll see a mid-16th century mansion, now a barracks of the Garde Républicaine. This brings us to a Frenchman no American Revolution in Paris tour can leave out: Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette. He was the first head of the Garde Nationale, which some see as a forerunner of the Garde Républicaine.

Joseph-Désiré Court

Portrait of Gilbert Motier the Marquis De La Fayette as a Lieutenant General 1791

Thomas Prichard Rossiter (1818–1871) and Louis Rémy Mignot (1831–1870)

Washington and Lafayette at Mount Vernon, 1784 (The Home of Washington after the War), 1859

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

In December 1776, La Fayette, then just 19, accepted an offer from American agent Silas Deane to become a major general in the American Army. Louis XVI, not yet won over to the American cause, forbade him to leave, but the wealthy young man bought a ship, dodged attempts to detain him and set sail on April 20, 1777. Exasperated with an influx of "French glory seekers," Congress at first gave La Fayette the cold shoulder, but came around once he said he'd serve for no pay. Benjamin Franklin recommended him as an aide-de-camp to General George Washington. On September 11, 1777, the young French officer was wounded at the Battle of Brandywine. After he played a key role in the victory at Yorktown, La Fayette's name became known throughout America.

FLASH QUIZ: How did Mount Vernon (Washington's Virgina home, now a museum) come to have the key to the Bastille?

ANSWER: In 1789, Lafayette gave the key to the newly fallen Bastille to Thomas Paine, who gave it to George Washington. (The key is approximately 6 inches long and weighs about one pound!)

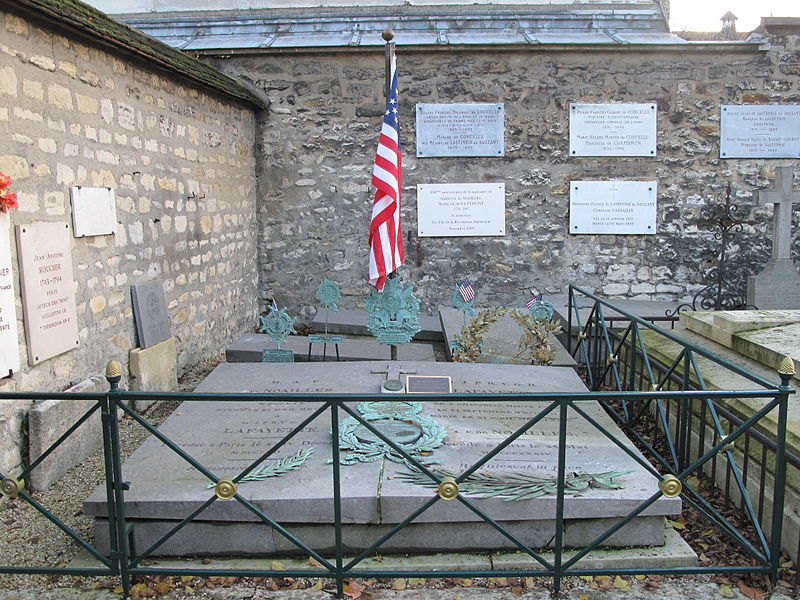

In French history there has probably been no greater Americanophile than La Fayette - who named his son George Washington La Fayette and a daughter Virginie. In 1824, La Fayette did a farewell tour of all 25 U.S. states, greeted by parades in major towns. Along the way he visited Thomas Jefferson in Monticello (they'd not seen each other for 35 years). La Fayette is buried in Paris's Picpus Cemetery next to his aristocrat wife, Adrienne de Noailles, whose relatives lie in a mass grave adjacent to the cemetery that contains some 1300 victims of the Reign of Terror. He is buried in American soil, which he brought back from his 1824 tour. The American flag on La Fayette's grave has never been taken down - even during the German occupation. Every July 4, the U.S. ambassador holds an extremely moving ceremony there.

Grave of the marquis de Lafayette and of his wife Adrienne in the cemetery of Picpus

Photo: Wikimedia, 2010

General John Pershing paying tribute at Lafayette's grave in Paris

Source: Wikimedia

Final Note

On July 4, 1826, 50 years to the day after the Declaration of Independence was signed, both Thomas Jefferson and John Adams died. Adams's last words were, "Jefferson lives," but in fact Jefferson had predeceased him.

By conservative estimate, America's independence cost France more than 1.3 billion livres, the equivalent of $13 billion today. As we have seen, France was crucial to American independence. We have also seen that without the work in France done by Silas Deane, Thomas Jefferson, Arthur Lee and especially Benjamin Franklin, American independence might never have come about.