Signing the Preliminary Treaty of Peace at Paris, November 30, 1782. John Jay and Benjamin Franklin standing at the left. Print by John D. Morris & Co. after painting by German artist Carl Wilhelm Anton Seiler (1846-1921)

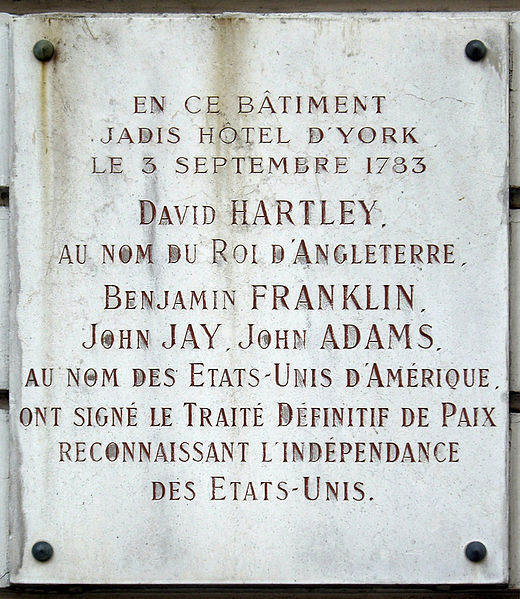

Plaque commemorating the signature of the Treaty of Paris by the American and British envoys, 1783

Auguste Couder (1790–1873)

Siege of Yorktown (1781), 1836

Palais de Versailles

John Trumbull (1756–1843)

Surrender of Lord Cornwallis

Rotunda of the US Capitol, Washington DC

This painting depicts the forces of British Major General Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis (1738-1805) (who was not himself present at the surrender), surrendering to French and American forces after the Siege of Yorktown (September 28 – October 19, 1781) during the American Revolutionary War.

Fireworks in front of the Hôtel de Ville in Paris to celebrate the peace treaty between France, the former American Colonies and Great Britain.

Original James Gillray caricature referencing the Treaty of Paris in 1783.

Two Treaties – Ben at His Best

As the plaque notes, this was the Hôtel de York, where on the morning of September 3, 1783, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams and John Jay signed the Treaty of Paris by which Britain, represented at the signing by David Hartley, recognized American independence. John Adams returned to the Hôtel de York with Abigail and their children for several days a year later. They then took a house in Auteuil, which, like Passy, was a village west of Paris in those days and is now part of the city. Later the Adamses moved to London, where John became America's first ambassador to the Court of St James's.

The peace sealed by the treaty was ultimately won in the Siege and Battle of Yorktown, where Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, Comte de Rochambeau, and his more than 5,000 French soldiers joined George Washington's Continental Army, and troops led by the Marquis de Lafayette, in forcing the surrender of the British commander Lord Cornwallis on October 19, 1781, following weeks of continuous bombardment by artillery and canon. While these troops had blocked a British escape by land, the escape by sea had been thwarted by the French naval fleet under the command of François Joseph Paul, Marquis de Grasse Tilly, Comte de Grasse, which had arrived from the then-French colony St-Domingue, now Haiti. (Statues and plaques honoring these French heroes grace certain areas of Paris's 16th arrondissement, on the Right Bank).

Benjamin in love

In 1782, while peace negotiations were still under way with the British, Benjamin Franklin included a different kind of treaty in a letter to Anne-Louise d'Hardancourt Brillon de Jouy, a musician nearly 40 years his junior with whom had been carrying on an intense, likely platonic, flirtation. A quarrel between them had evidently inspired the following:

I fancy we shall neither of us get any thing by this War, and therefore as feeling my self the Weakest, I will do what indeed ought always to be done by the Wisest, be first in making the Propositions for Peace. That a Peace may be lasting, the Articles of the Treaty should be regulated upon the Principles of the most perfect Equity & Reciprocity. In this View I have drawn up & offer the following, viz. -

ARTICLE 1.

There shall be eternal Peace, Friendship & Love, between Madame B. and Mr F.

ARTICLE 2.

In order to maintain the same inviolably, Made B. on her Part stipulates and agrees, that Mr F. shall come to her whenever she sends for him.

ARTICLE 3.

That he shall stay with her as long as she pleases.

ARTICLE 4.

That when he is with her, he shall be oblig'd to drink Tea, play Chess, hear Musick; or do any other thing that she requires of him.

ARTICLE 5.

And that he shall love no other Woman but herself.

ARTICLE 6.

And the said Mr F. on his part stipulates and agrees, that he will go away from M. B.'s whenever he pleases.

ARTICLE 7.

That he will stay away as long as he pleases.

ARTICLE 8.

That when he is with her, he will do what he pleases.

ARTICLE 9.

And that he will love any other Woman as far as he finds her amiable.

Let me know what you think of these Preliminaries. To me they seem to express the true Meaning and Intention of each Party more plainly than most Treaties. - I shall insist pretty strongly on the eighth Article, tho' without much Hope of your Consent to it; and on the ninth also, tho I despair of ever finding any other Woman that I could love with equal Tenderness: being ever, my dear dear Friend, Yours most sincerely.

Anne-Louise Brillon de Jouy

While Franklin was discovering the charms of French women, the French soldiers and officers who had ventured to America to fight side by side with their allies also shared their impressions of the customs and people found in the New World.

French Gallantry in America

The young Frenchmen who served in the American Revolution were greatly interested in the "character and conduct of our women," notes historian and congressman James Breck Perkins in France in the American Revolution (1911).

"They were surprised at the freedom with which women met them, yet they had sense enough to realize that the women were not in love with them, but that such were the usages of a society in which intrigues were unknown. The contrast between the freedom of our young girls and the strictness with which the French jeune fille is guarded constantly impressed our visitors. One of them was a little shocked when he found even so staid a personage as Samuel Adams [then age 60] tete-a-tete with a young girl of fifteen, who was preparing his tea." Perkins continued, "The strictness of the married women surprised them as much as the freedom of the unmarried." He cites the complaint of Rochambeau, commander of the French expeditionary force, that when a young American woman discovered that one of the visitors was married she would have nothing more to do with him.

Perkins adds that the French felt American women to be generally lacking in the social charm and accomplishments that would be expected in French women or similar station. One officer stated, "Making tea and seeing that the house is kept clean constitute the whole of their domestic province" – in contrast to Parisian ladies' "familiarity with art in all its forms, and a degree of skill in many of them, a knowledge of literature, a brilliancy of conversation, which to say the least was much less common among the women of the Revolution." Still, the visitors appreciated the simplicity of the Americans, compared with what was coming to be perceived as the exaggerated ways of French women:

"A certain weariness of elaborate dress and conventional modes of life had already manifested itself in Paris," Perkins writes. "The ardent youths of the period were ready to be favorably affected by different ideals. It was not only the natural ardor of youth for a pretty woman, but a reaction from the life to which he had been accustomed, that excited the Prince de Broglie's enthusiasm when he met Polly Leiton," a young Quaker. The prince noted in his journal: "The simplicity of her dress gave to Polly the air of a Holy Virgin, and to this the modesty of her speech and the grace of her bearing corresponded. I confess, this beguiling Polly seemed to be the chef-d'oeuvre of nature, and whenever her image presents itself to me, I form the plan of writing a large book against the attire … the coquetry, and factitious charms of various women that are admired in the world."

Another fan of Polly was Louis Philippe, comte de Ségur, who claims in his memoirs: "So much beauty, so much simplicity, so much elegance, so much modesty, were perhaps never before combined in the same person. … In truth, I was tempted to believe that she was a celestial being. Had I not been married and happy, I should, while coming to defend the liberty of Americans, have lost my own at the feet of Polly Leiton."

Ségur, who would later sympathize with the aims of the French Revolution and later still, serve under Bonaparte, also admired the new land itself. "He was charmed alike by the beauties of virgin forests, and fields that had not yet known the plow, and by the spectacle of prosperity and thrift where civilization had already found its way," Perkins writes. "Wherever he stopped, he tells us, he was received with simplicity of manner, courtesy and urbanity. He met neither poverty nor vice, but everywhere ease and contentment, with neither the prejudices nor the servility of European society. To such blessings, he added, that if the fare was simple, it was everywhere abundant; that if the rum was too strong and the coffee too weak, the tea was excellent."

A Lot of Gold

If you're facing the plaque, turn right and walk to number 52 of the rue Jacob.

This was the Hôtel de Hambourg, where Benjamin Franklin spent January and February 1777 (before moving to Passy). Here he received notification that King Louis XVI was allocating 2 million livres toward the purchase of arms and supplies for the American Revolution–some $37 million in today's money.