Introduction

The Museum

The Museum of Mediterranean Masks was established with the aim of creating a meeting place between the cultural universe of Mamoiada – a town in the heart of Sardinia, with its world-renowned traditional masked figures known as Mamuthones and Issohadores – and other Mediterranean regions, underlining their close historical and cultural relationship through their pre-Lenten Carnival celebrations and attire.

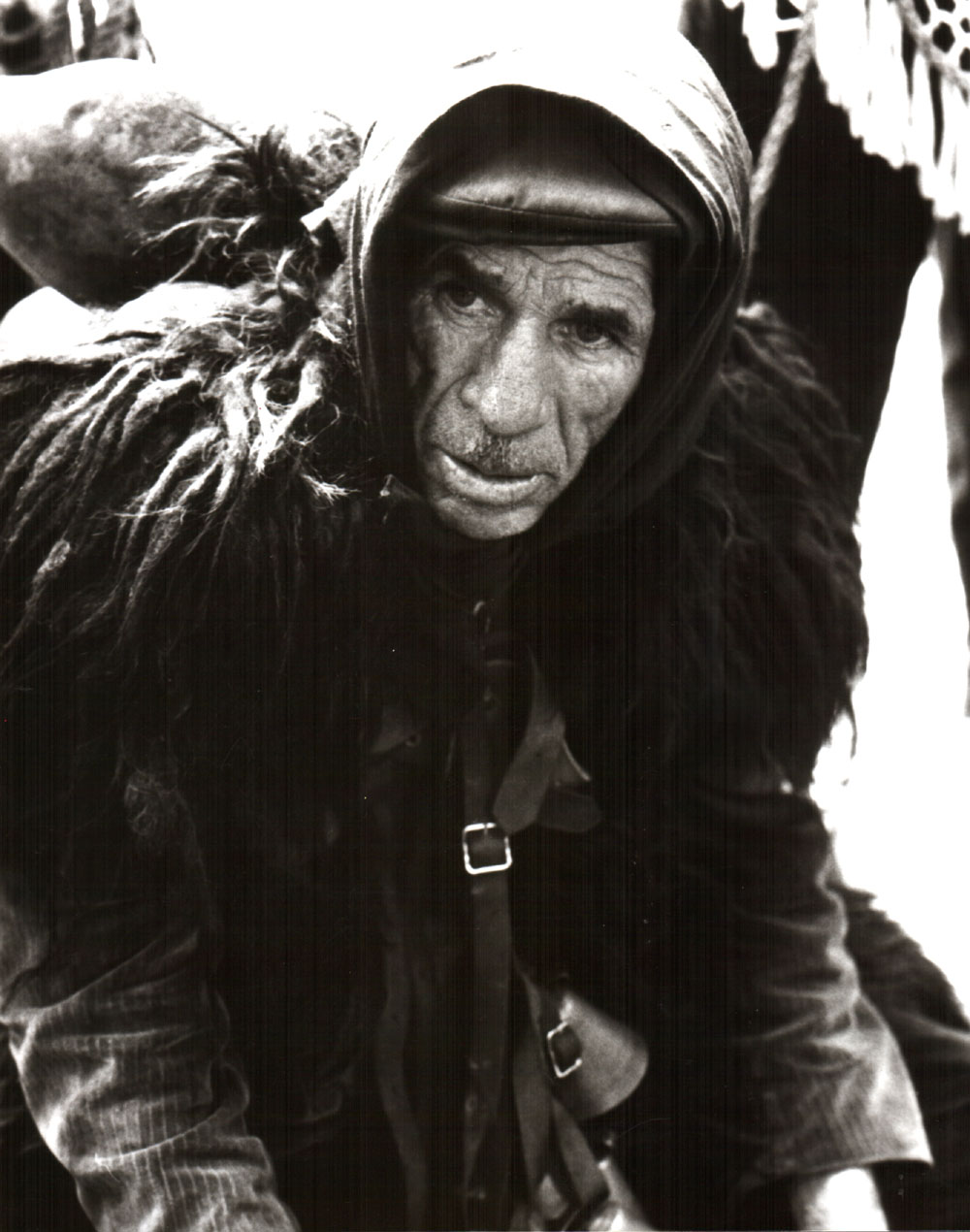

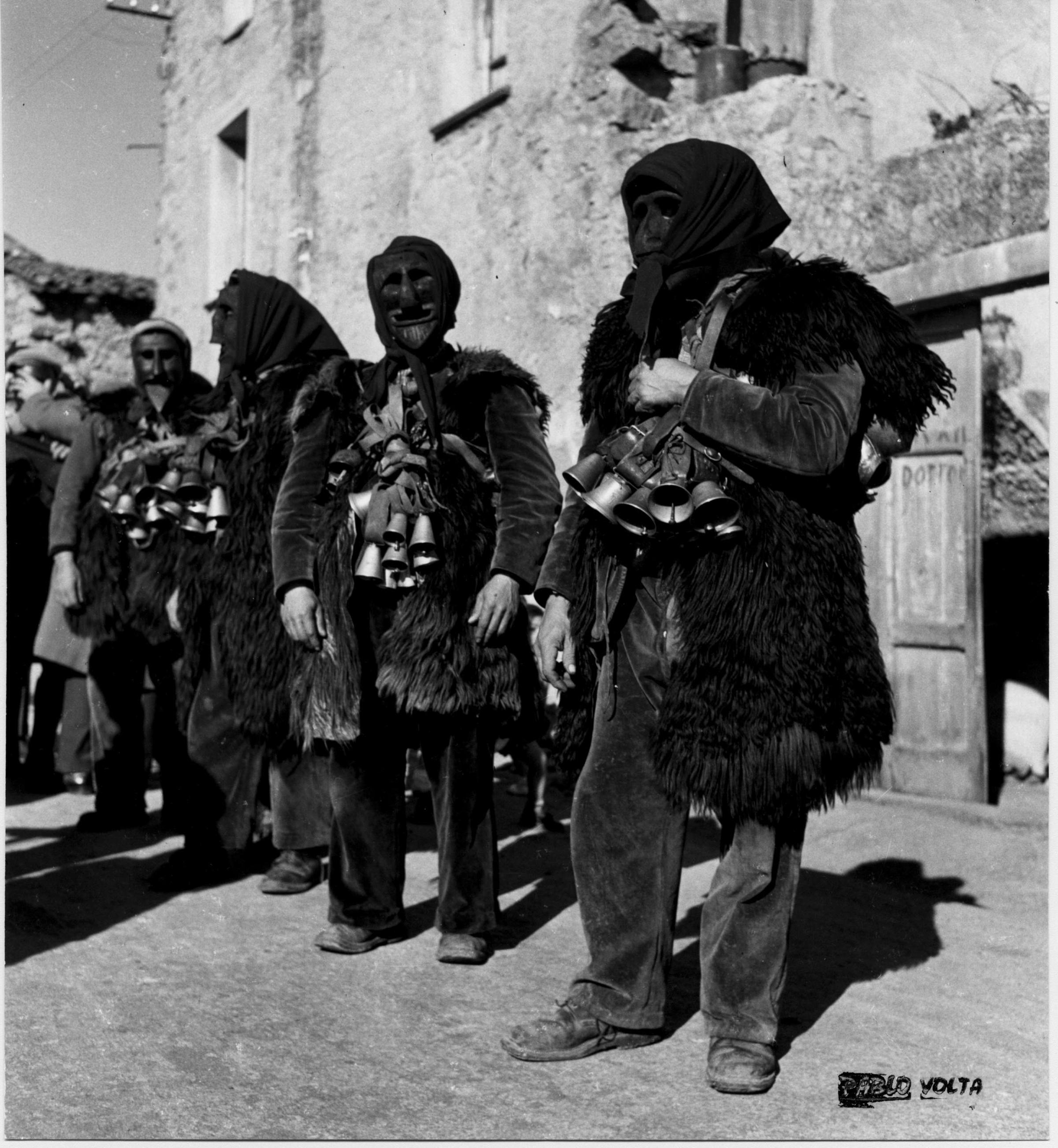

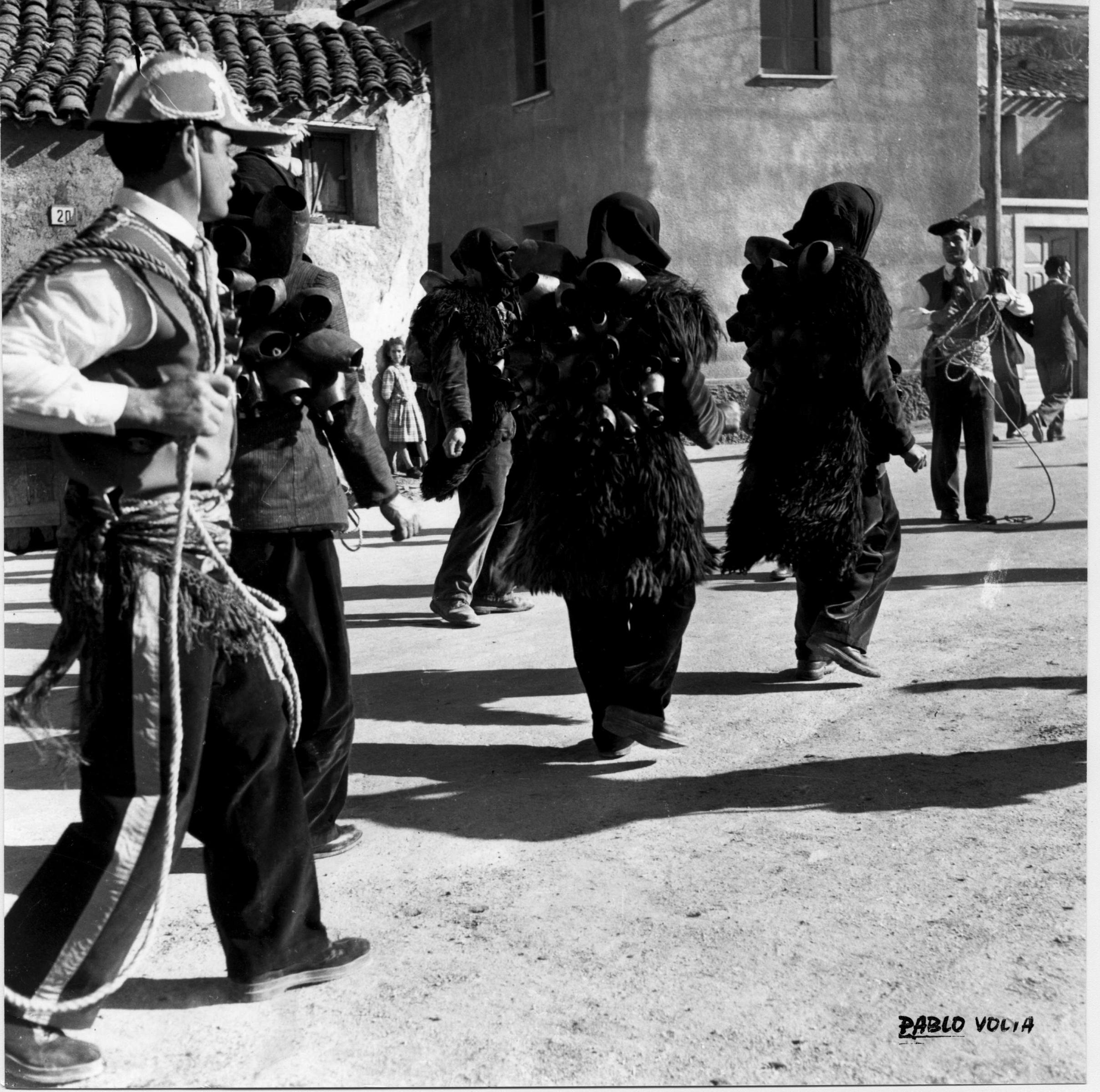

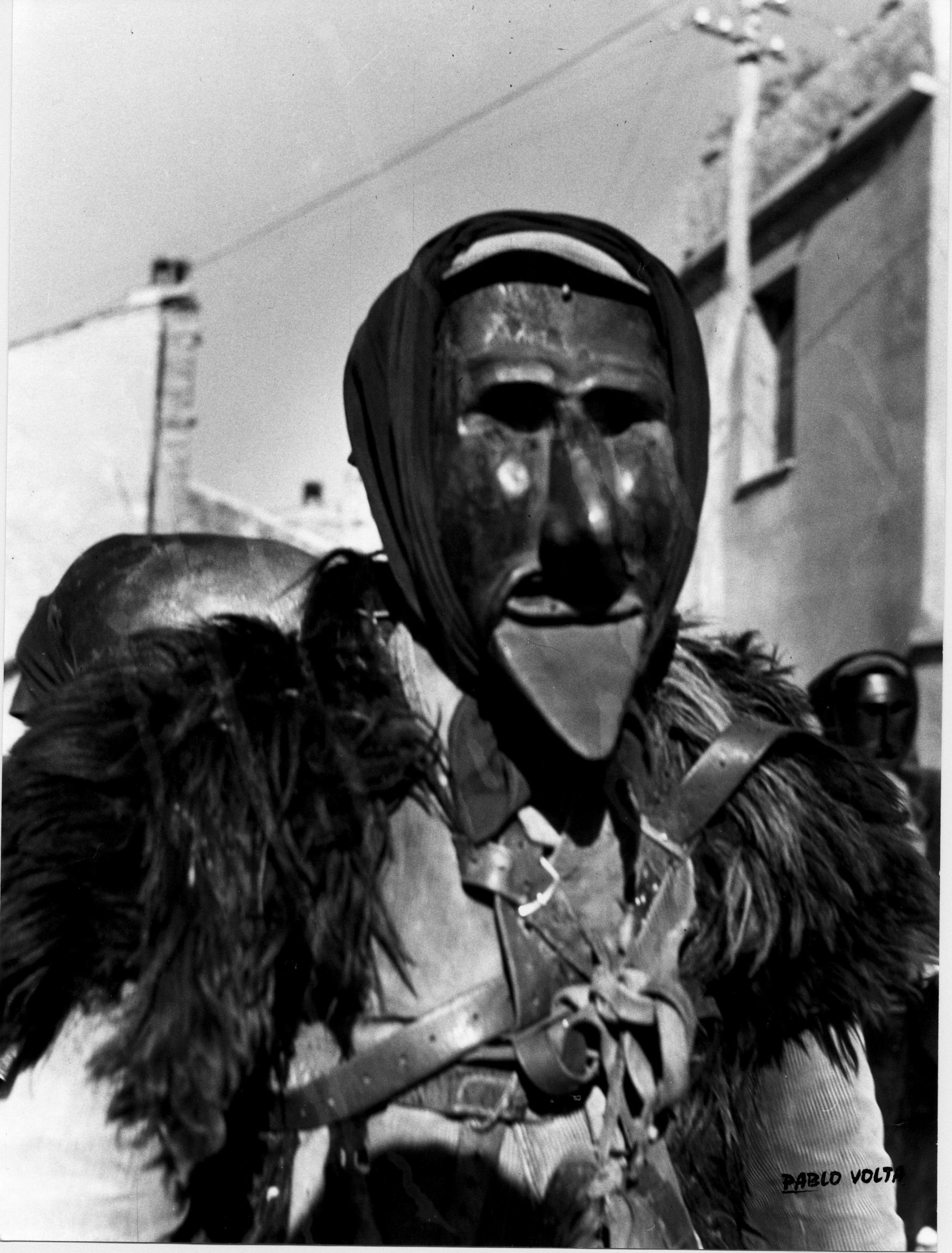

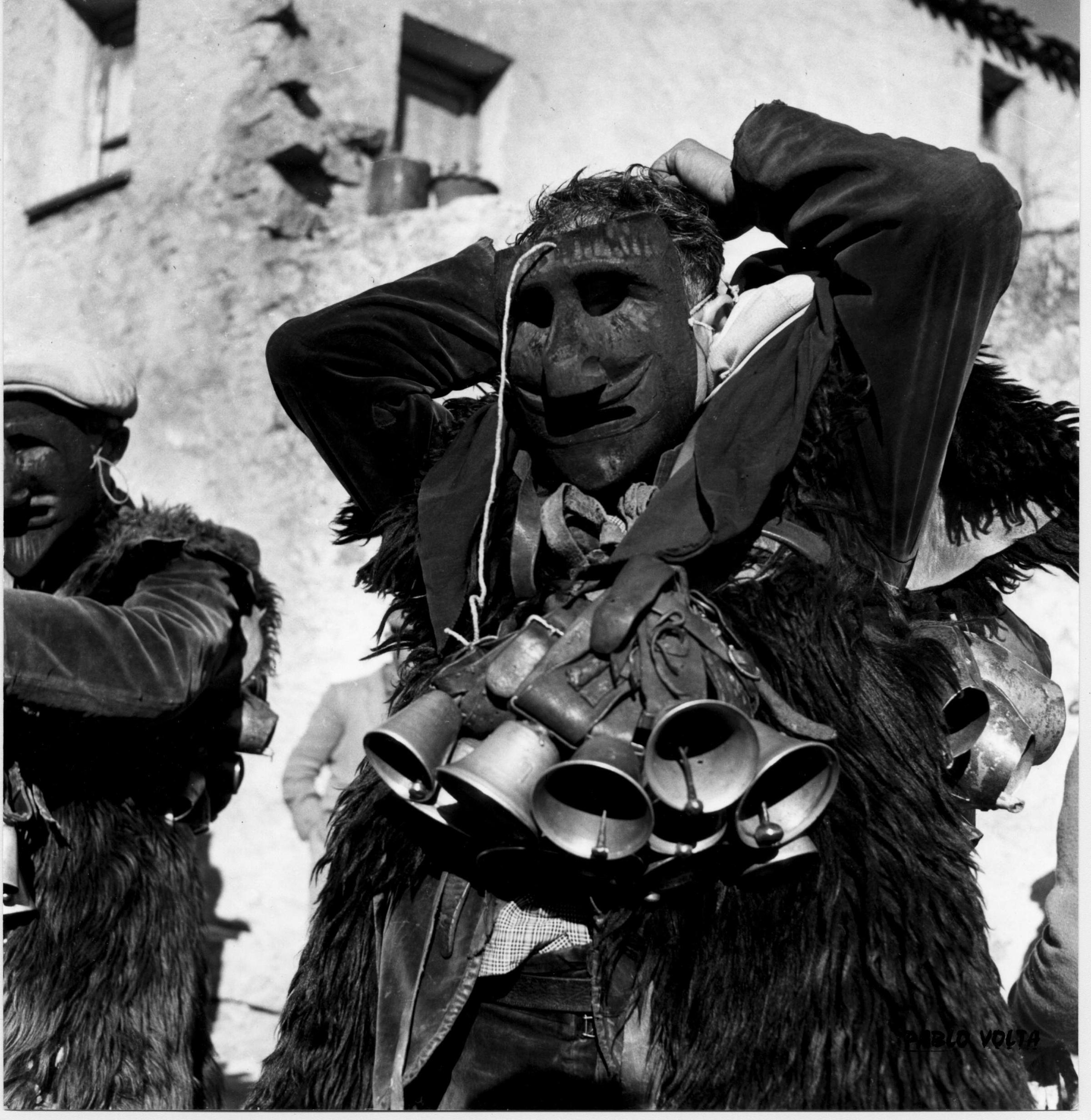

The museum focuses on ritual costumes representing traditional characters. The costumes combine a wide array of zoomorphic and grotesque masks, usually carved in wood, with sheepskins, bells and other objects that make a lot of noise. (In Italian, the word “mask” may refer not only to the face covering but also to the ritual costume as a whole and to the age-old character it represents, and this is how the museum often uses it.)

These characters, originating in traditional herding and farming communities, may once have been thought to be capable of influencing the seasons and ensuring an abundant harvest. Therefore, despite their fearsome appearance, their arrival was eagerly awaited and much appreciated: everyone would flatter them and try to win their friendship by offering them food and drink.

The Museum poster

Mamoiada, external view of the museum

Mamoiada, carnival parade

Mamoiada, carnival parade

Mamoiada, carnival parade

Beginning with masks from Mamoiada, the museum offers a collection comparing objects from several Mediterranean countries, highlighting their similarities more than their differences.

The current arrangement of the collection constitutes the first stage of an ambitious project of the museum, the intent of which is to cover the whole range of masks from agricultural and pastoral societies throughout the Mediterranean, and to create a documentation center on Carnival and masquerade traditions. There is a natural connection between the museum’s activities and various cultural and touristic initiatives in and around Mamoiada. The museum is an important focal point providing information, organizing tours in the region and enabling visitors to attend traditional events and festivals – most notably the Carnival celebrations – as well as promoting local craft and food products.

Historical roots

Mamoiada, carnival parade

Mamoiada, carnival parade

Mamoiada, carnival parade

Mamoiada, carnival parade

Mamoiada, carnival parade

Mamoiada, carnival parade

Mamoiada, carnival parade

The origins and meaning of the masked figures of Mamoiada are lost in the mist of time and remain rather mysterious today. Raffaello Marchi, a local artist and scholar, was the first to study them. In an article published in 1951 in the magazine Il Ponte, he proposed that these masks represented the struggle of the Sardinians against the Arab incursions that began in the 8th century. Marchi speculated that the mournful-looking Mamuthones – who march in two columns at a slow, rhythmic pace – represented the vanquished while the Issohadores, who surround the procession like guards, represented the victors. More recently, research has turned to another theory, which suggests the masks were used in a propitiatory rite carried out by farmers and herders at the beginning of the agricultural year in hopes that their harvests and flocks would be abundant. Yet another interpretation is that of the cultural anthropologist Dolores Turchi, who held that the masks represented a tragic and Dionysian death ritual based on the contrast between negative and positive elements that were both opposing and complementary: the Mamuthones, in this view, represent darkness and the death of nature while the Issohadores represent youth, light and the rebirth of nature in the spring. There are twelve Mamuthones, like the months of the year, and they seem to be moving toward sacrifice, to die and be reborn every year, as in the natural cycle of cereal crops. And there are still other theories based on the centrality of the relationship between humans and animals, which may be celebrated allegorically by inverting the roles of human and beast.