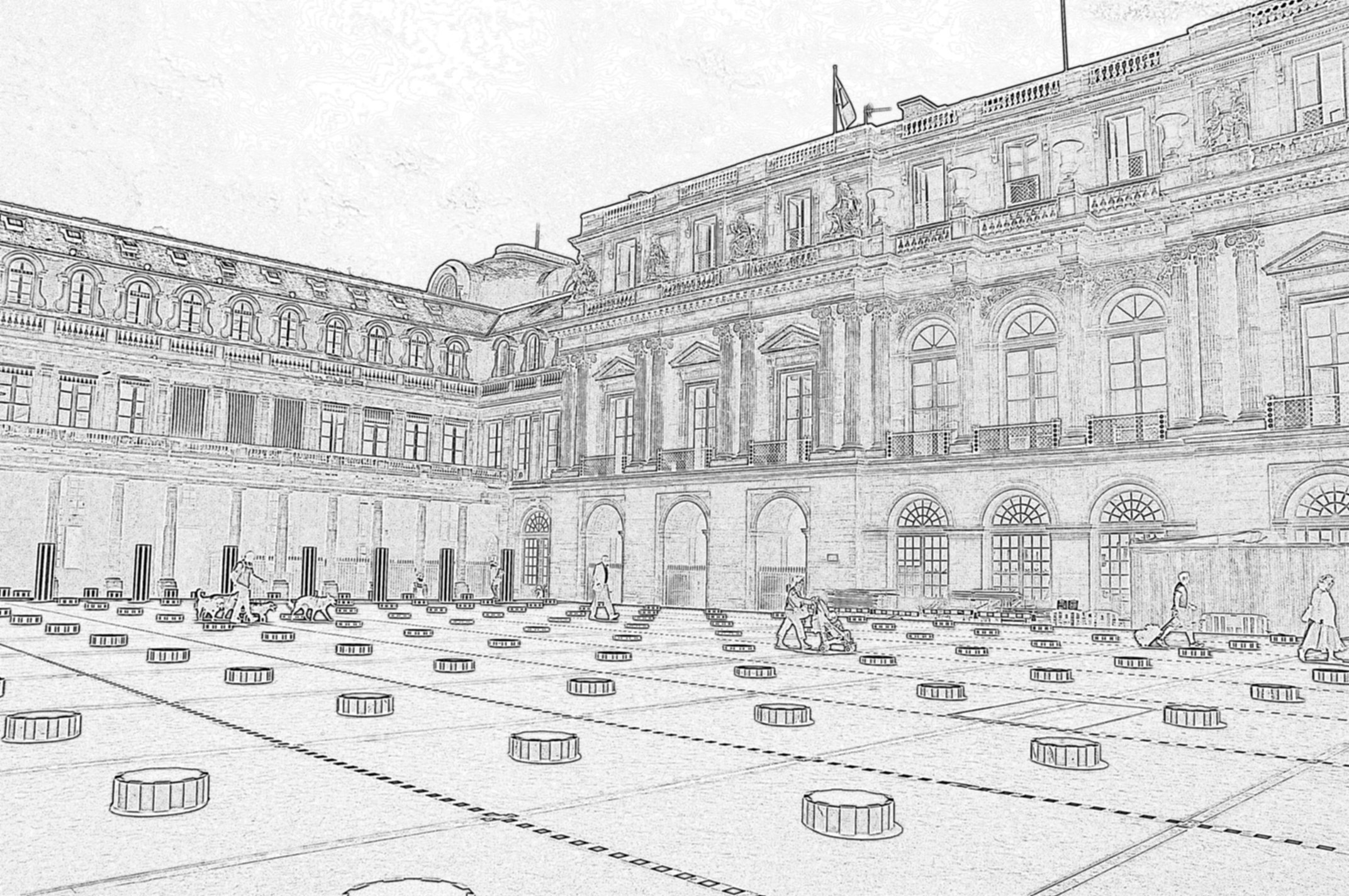

Frederick Nash,

The Cour d'Honneur of the Palais-Royal, 1829

pen-and-ink drawing, brown ink wash and watercolor

(Paris, Bibliothèque nationale).

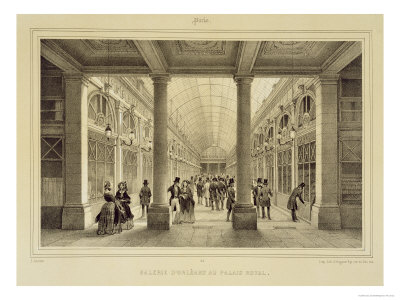

Colored engraving of the Galerie d'Orléans,

circa 1830

(Paris, Musée Carnavalet).

The electrical plant installed in the Cour d'Honneur of the Palais-Royal between 1888 and the 1920s.

View from June 14, 1913.

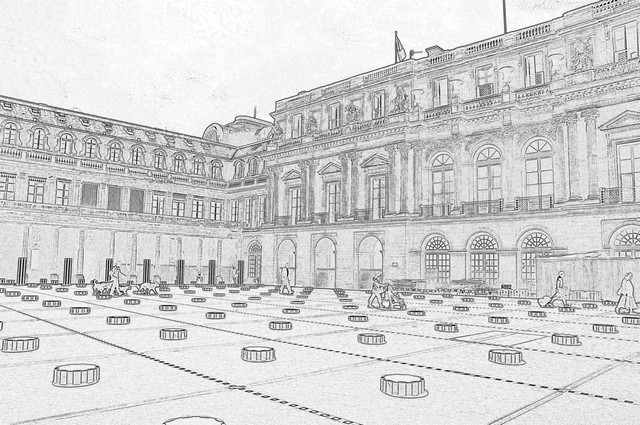

The Cour d'Honneur of the Palais-Royal

today

© Blue Lion (2012)

The Cour d'Honneur of the Palais-Royal today

© Blue Lion (2012)

The Cour d'Honneur

Buren's columns

Entering the second courtyard (the internal courtyard), you are surrounded by multiple black and white columns of all sizes, emerging from the ground like growing trees. Looking into the well in this courtyard, the columns seem to extend underground which explains the title of this in situ piece of art: Les deux plateaux (The Two Levels). In 1986, under the presidency of François Mitterrand, the courtyard was further embellished with a sculpture by the artist Daniel Buren, commissioned by the Ministry of Culture and Communication, accommodated in the Galerie des Proues (Gallery of the Bows) of the Palais-Royal. This sculpture figures among Grands Projets of President Mitterrand, who in the 1980s decided to transform the museum city into a modern one by introducing contemporary art and architecture. Buren is a founding member of the group BMPT (Buren, Mosset, Parmentier and Toroni), which, in the spirit of the 1960s, seeks to bring artwork down from its pedestal, out of museums and galleries in order to make it accessible to the general public. Art and life would thus be intermingled. In an ideal case, an object of everyday life is elevated to the status of art work and each and everyone can be involved. Gazing towards the windows, we discover the awnings striped in gray and white, identical to the design of the columns, conveying the idea of a ready-made pattern. Following the concept of Marcel Duchamp, the prefabricated object is elevated to the level of art work by the artist's mere choice rather than by a creative act.

But why these columns? Turning towards the garden, we see two rows of columns connecting the Montpensier and Valois galleries, which once formed the magnificent Galerie d'Orléans, covered at the time with an elegant glass ceiling. It was designed by Pierre Fontaine, the former architect of Napoleon Bonaparte, and commissioned by the Duke of Orleans (later King Louis-Philippe) around 1829 to accommodate shops, becoming the prototype of the Parisian covered galleries. Of the Galerie d'Orléans, destroyed in 1935, only two rows of columns remain today, supporting a terrace which connects the two wings of the Palace at the level of the first floor.

The Galerie d'Orléans at the Palais-Royal,

lithograph by Gihaut Frères, from a drawing by Ph. Benoist,

2d half of the 19th century.

The Galerie d'Orléans itself was built in 1789 on the site of two older wooden galleries called "Camp des Tartares". It appears that, at the end of the 17th century, Philippe I, Duke of Orleans, had already erected a wooden gallery to display his art collection.

The wooden galleries.

View of the wooden galleries,

before the construction of the Galerie d'Orléans.

Engraving, between 1789 and 1827

(Paris, Musée Carnavalet).

But let us go back to Buren. The artist seems to mock the "folly of the columns", Fontaine ha conceived in the Galerie d'Orléans as a symbol of power. With Buren, the pillar whose strength and stability formerly supported portals and roofs, has lost its function, was rendered futile, just like the power of the French monarchy gave way to democracy on this very site. Buren proposes a parallel between the power of the artist and that of the onlooker. Here too, the interaction has been democratized, which applies also to both the kinetic fountains built in 1985 by Pol Bury.

Pol Bury, Sphérades

Pol Bury,

Sphérades foutains, Palais-Royal, 1985.

© Adagp, Paris 2012,

Photo: © Antonio Ca' Zorzi (2011)

Pol Bury,

Sphérades foutains, Palais-Royal, 1985.

© Adagp, Paris 2012,

Photo: © Antonio Ca' Zorzi (2011)

These invite the visitor to appropriate the work of art: stainless steel mobile spheres placed above the water. The spectator is free to touch and move them. Here art is a game and, at the same time, also connects to science; by mirroring the space around them, these spheres capture the macrocosm in a microcosm.

The Facades around the Courtyard

The Cour d’Honneur

Facade in the Cour d’Honneur,

by Contant d’Ivry.

© Blue Lion

The Galerie des Proues (Gallery of Bows)

© Blue Lion

The main building on the second courtyard was designed by Contant d'Ivry. The facade has two front bodies decorated in a classical style with sculptures symbolizing military skill, prudence, liberality and the arts.

The building now houses the State Council. On the side of the Galerie de Valois, the Galerie des Proues (Gallery of Bows) is the last remnant of the palace built after 1624 by Cardinal Richelieu, who wanted to stay close to King Louis XIII. Here, in the heart of Paris that power was held and conspiracies repressed. He called the King's architect, Jacques Lemercier, who had just built the Pavilion of the Clock in the Louvre courtyard. For the Cardinal, now the King's First Minister and Minister of the Navy, Lemercier designed the main building between a courtyard and a garden in the classical style. At the time the garden would have extended to infinity,h ad it not been surrounded by the walls of Charles V’s fortress, which Richelieu later demolished. On the facade of the Galerie des Proues you will find the ornamental prows of ships with anchors attached, symbols of navigation and stability, reminders of the Cardinal's political role.

Galerie des Proues, ornamental prows of ships

© Wikimedia (2010)

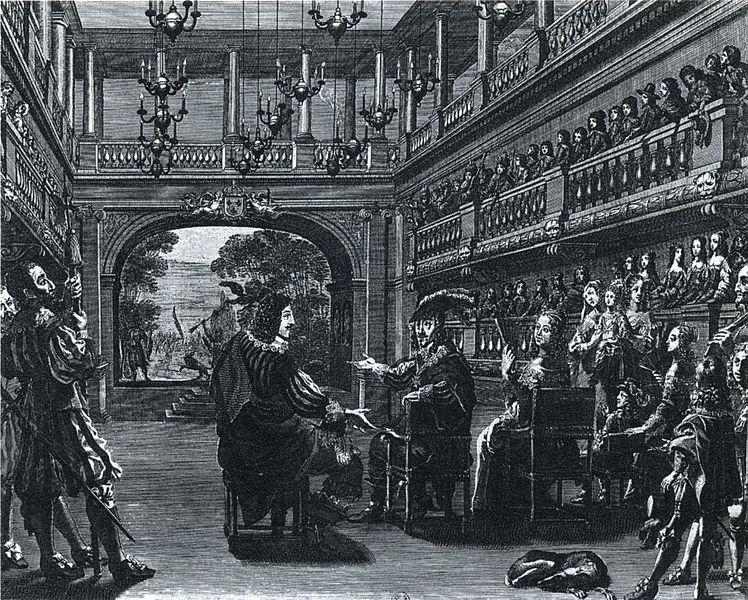

In his new palace Richelieu built two theaters where plays were performed, mostly written by the so-called Group of the Five Authors (including Pierre Corneille), who worked and met regularly under the Cardinal's direction. Richelieu was passionate about literature and theater. Well conscious of the latter's potential as means of communication he conceived, commissioned and occasionally co-auhored works that served his vast political designs.

Theatre of the Palais-Cardinal.

Jean de Saint-Igny,

Performance of "Mirame" at the Palais-Cardinal in front of Louis XIII, Richelieu and Anne of Austria,

24 January 1641,

engraving.

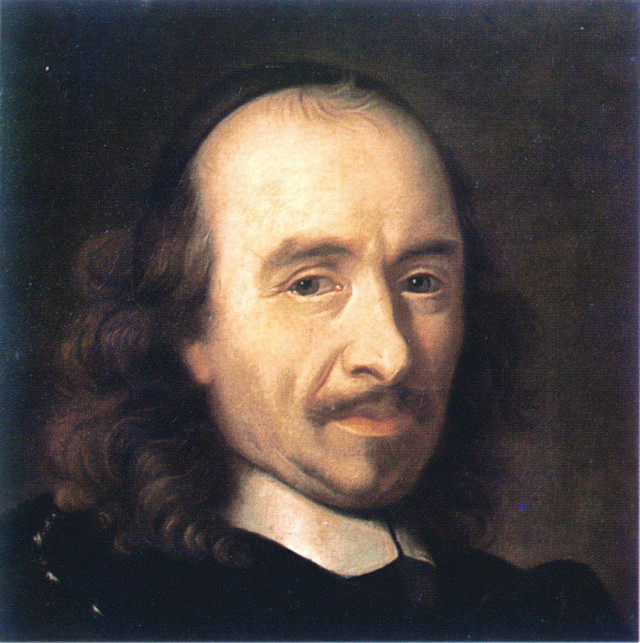

French School of the 17th century,

Portrait of Pierre Corneille (detail)

Oil on canvas, 1647

Musée national du château de Versailles

As to the relationship between the Corneille and Richelieu, there is no definite consensus on a presumed conflict. While Corneille's innovating masterpiece, Le Cid, caused a stir and met with a reprimand from the French Academy for not respecting the traditional unity of time, place and action, we know that it was also twice performed in the Cardinal's private theater.

Asserting his authority in the literary world, in 1635 the Cardinal established the prestigious Académie Française, an institution acting as the official authority on the French language, charged with publishing and updating the official dictionary. It is still composed of forty members (the "Immortals") from French literary circles and, by tradition, also from high military ranks, statesmen and religious dignitaries. Members from other French speaking countries and women were admitted only rather recently.

On his deathbed, in 1642, the Cardinal bequeathed his palace to Louis XIII, who was also ill and died a few months later. Now it became the Palais Royal, residence of Anne of Austria, the king's widow, her two small sons, Louis XIV and Philippe, later Duke of Orleans and her adviser, Cardinal Mazarin. It was a time of great turmoil and revolts, and the royal family soon moved to the Castle of Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

In 1661, the palace became the residence of Louis XIV's younger brother and hence the main residence of the Dukes of Orleans.