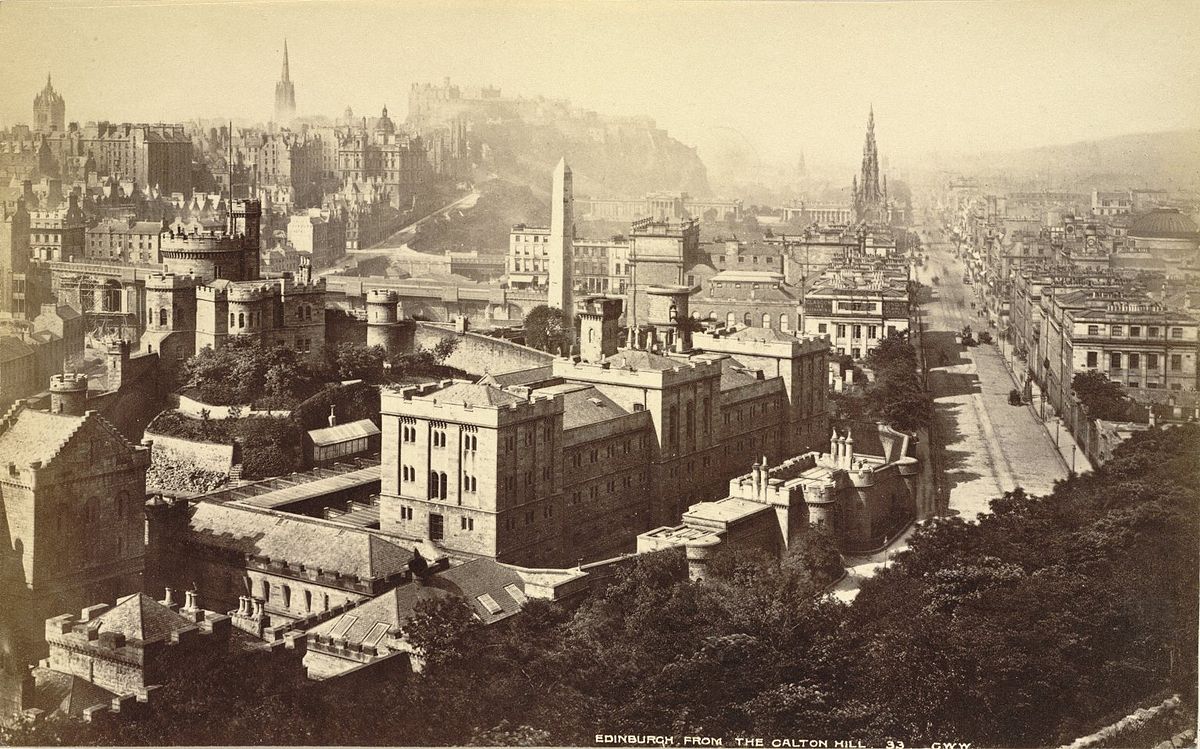

View of Edinburgh

Samuel by Dukinfield Swarbreck (attr), 1827

Edinburgh from Calton Hill

Photograph: George Washington Wilson, 1865

The Cradle of Scottish Enlightenment

So is the case with the Edinburgh Enlightenment, which is often said to have flourished for a century beginning around 1740. But this obscures the fact that it did so on a foundation of decades of education and enterprise, as well as, ironically, historical deprivation, poverty and adversity. Time is not the only questionable dimension here, because restricting discussion to Edinburgh ignores the fact that, in reality, the Scottish Enlightenment thrived in all four of the country’s university cities: Glasgow, Edinburgh, St. Andrews and Aberdeen. Indeed, if philosophical pre-eminence is to be considered the hallmark of the enlightenment, then it could be argued that the Enlightenment was born in Glasgow with the first internationally renowned Scottish philosopher, Francis Hutcheson, who took up the chair of Moral Philosophy at Glasgow University in 1729. In turn, Hutcheson taught and greatly influenced Adam Smith, author of the Wealth of Nations, one of the cornerstones of classical economics based on philosophical premises. Hutcheson’s most famous work, A System of Moral Philosophy, was also the starting point for much of the early thinking of David Hume, who arguably became Scotland’s greatest philosopher.

Francis Hutcheson by Allan Ramsay (1713-1784)

Hunterian Museum and Gallery

Leaving aside the question of its birth, it can be stated unequivocally that the Scottish Enlightenment was cradled, nurtured and reached its zenith in Edinburgh, where a veritable storm of intellectual fervour accompanied the extension of a squalid, overcrowded and almost medieval Old Town into the elegant Georgian marvel of urban planning known as the New Town. This transformation might even be considered miraculous, given that it took place after the collapse of the economy as a result of the disastrous and ill-conceived colonization effort in the Isthmus of Panama (known as the Darien scheme), the removal of the Scottish Parliament following Union with England in 1707 and the failed Jacobite rebellions of 1715 and 1745, ending in the bloody massacre of Culloden. As alluded to earlier, it could be that intellectual progress can be spurred onwards by such adversity, perhaps in Edinburgh’s case, with the hope of ameliorating the city’s generally dire circumstances. But, the critical factor in Scotland’s case was probably its surprisingly advanced education system. As the civil rights activist Derrick Bell has written:

“Education leads to enlightenment. Enlightenment opens the way to empathy. Empathy foreshadows reform.”

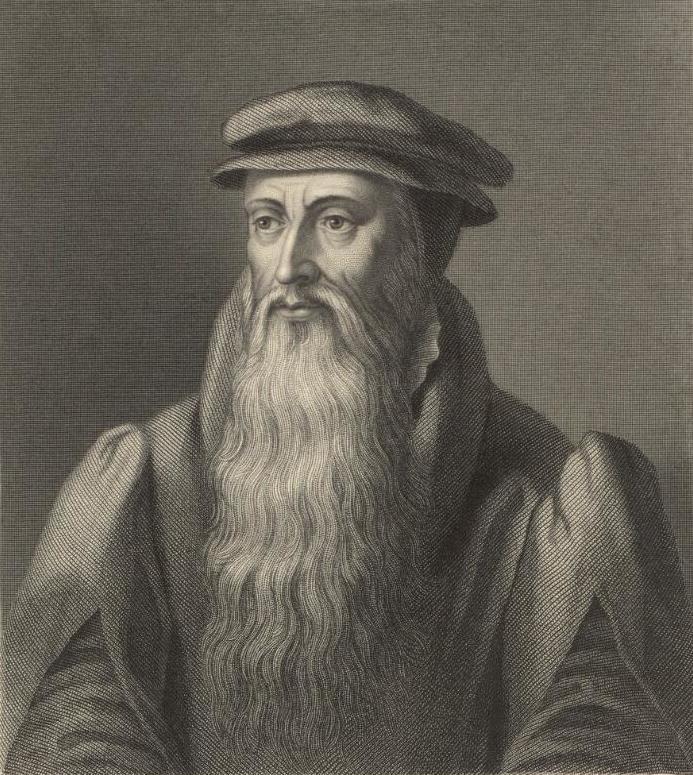

Where did Scotland’s superiority in education spring from? The reader of this guide will find one of the answers when embarking on the Old Town Walk. One of the early stops of the walk will be in St. Giles Cathedral, where there is an arresting statue of John Knox, the Scottish theologian, writer, leader of the reformation and founder of the Presbyterian Church of Scotland.

John Knox by William Holl (1807-1871)

National Library of Wales

As the author of the remarkable diatribe The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women (1558), Knox might seem an unlikely contributor to the progressive thinking of the Scottish Enlightenment two centuries later. However, the reformed church understood the need to educate the population in order that they could read the bible. John Knox championed this cause, despite the poverty of the country, writing as follows:

"Therefore, we judge it necessary that every several church have a schoolmaster appointed, such a one as is able, at least, to teach Grammar and the Latin tongue, if the town be of any reputation. If it be rural then must either the Reader or the Minister there appointed take care over the children and youth of the parish, to instruct them in their first rudiments, and especially in the Catechism. And further, we think it expedient that in every notable town there be erected a High School in which the Arts, at least Logic and Rhetoric, together with the tongues, shall be read by sufficient masters, for whom honest stipends must be appointed. Lastly, the great schools called Universities shall be replenished with those apt for learning."

The results were spectacular. By the time of the Enlightenment, Scotland had the highest standard of literacy of any European nation and had four universities, in contrast to only two in England. The ensuing flourishing of culture was perhaps an unintended outcome of Knox’s actions, but his legacy is clear.

But an additional factor is relevant to the development of Scotland’s education. The country had longstanding associations with continental Europe, beginning with The Auld Alliance between Scotland and France, an agreement first signed in 1295 between King John Balliol of Scotland and Phillip IV of France. Relations with France, the Netherlands, Sweden, Poland and Russia developed over the years and by the 18th century, Scotland had an extensive network of political, economic and educational links across Europe. The country’s universities developed educational systems and curricula influenced by their continental contemporaries. In some cases, this was so successful that the Scottish schools attained pre-eminence, as in the case of Edinburgh Medical School, which by the 1740s had supplanted Leiden as the major centre of medicine in Europe. The long tradition of relations with France also meant that the two countries exchanged education, philosophy and thinking throughout the Enlightenment, although Scotland’s version eventually advanced along a different pathway as described further below.

Whatever the historical or geographic factors involved, from the mid-eighteenth century onwards the Enlightenment was ignited in Edinburgh, led by the educated classes who did not follow their political and aristocratic contemporaries to London following the Union in 1707. Law, theology, universities and the medical establishment engaged in feverish activity and discussion, such that over subsequent decades remarkable advances were made in philosophy, political economy, engineering, architecture, medicine, geology, archaeology, law, agriculture, chemistry and sociology. Impresarios of these disciplines engaged in intense discussion at fora such as The Select Society, which first met in the Advocate’s Library on November 12th, 1754. In March 1755, ‘An Account of the Select Socieit [sic] of Edinburgh’ was published in The Scots Magazine, informing the public that:

"The intention of the gentlemen was, by practice to improve themselves in reasoning and eloquence, and by the freedom of debate, to discover the most effectual methods of promoting the good of the country."

The society’s members included key figures of the enlightenment such as James Burnett, Lord Monboddo, George Drummond, Adam Ferguson, Francis Home, Lord Kames, David Hume, Allan Ramsay, William Robertson and Adam Smith.

Res_Robert Burns and Lord Monboddo by John Edgar (1819 - 1876)

Scottish National Gallery.jpg

Light relief from such intellectual debate was provided by more convivial groups such as the Poker Club and the Crochallan Fencibles, where boisterous activity was facilitated by copious quantities of alcohol and bawdy songs. Robert Burns compiled a book of popular songs for the Crochallan Fencibles, entitled The Merry Muses of Caledonia, no doubt tame by today’s standards, but somewhat scandalous at the time. Perhaps these meetings served their purpose, for even the famous Scottish philosopher, David Hume had this to say of the Poker Club:

"Most fortunately it happens that since reason is incapable of dispelling these clouds, nature herself suffices to that purpose ... I dine, I play a game of backgammon, I converse, and am merry with my friends; and when after three or four hours amusement, I return to these speculations, they appear so cold, and strain'd, and ridiculous, that I cannot find it in my heart to enter into them any farther."

And yet he went on to pen some of the most influential philosophical thinking of his time. For the reader whose primary interest is philosophy, David Hume’s A Treatise of Human Nature is worthy of attention as one of the seminal contributions to the Scottish Enlightenment, focusing, as it did on the psychological basis of human nature and his associated scepticism about human powers of reason. Hume wrote that:

"Tis evident, that all the sciences have a relation, more or less, to human nature ... Even Mathematics, Natural Philosophy, and Natural Religion, are in some measure dependent on the science of Man."

David Hume by Allan Ramsay (1713-1784)

Scottish National Gallery

Despite how influential Hume’s writings proved to be, as Edinburgh’s atmosphere of fervent debate progressed, there was an inevitable reaction to his scepticism, in the form of a second major strand of philosophical thought, developed among others by Dugald Stewart and Thomas Reid. Through emphasis on mankind’s capacity of rational thinking, they advanced a philosophy of “common sense” commonly referred to as Scottish common-sense realism. This school ultimately had substantial impact in continental Europe and the United States. Thomas Reid encapsulated this thinking as follows:

“If there are certain principles, as I think there are, which the constitution of our nature leads us to believe, and which we are under a necessity to take for granted in the common concerns of life, without being able to give a reason for them — these are what we call the principles of common sense; and what is manifestly contrary to them, is what we call absurd.”

Nonetheless, although on the surface, Hume and Reid represented conflicting philosophical schools of thought, they both were concerned primarily with the study of man and human nature. And whereas their French counterparts focused exclusively on the power of reason in the form of Cartesian principles, the Scots put more emphasis on sentiments, arguing that people are born with moral emotions, an innate sense of justice and common sense. In a similar vein they recognized that individuals are also moved by less benevolent passions, such as intense will to survive and tribalism. The common-sense approach encompassed all of this and contributed to very practical outcomes. In contrast to the French pursuit of philosophical thought as an end in itself, the Scottish Enlightenment engendered concrete applications in science, medicine, economics, law and agriculture. In turn this significantly fed into an economic revival for Scotland, which had previously been relegated to the poorest country in Europe, primarily as a consequence of the failed Darien scheme.

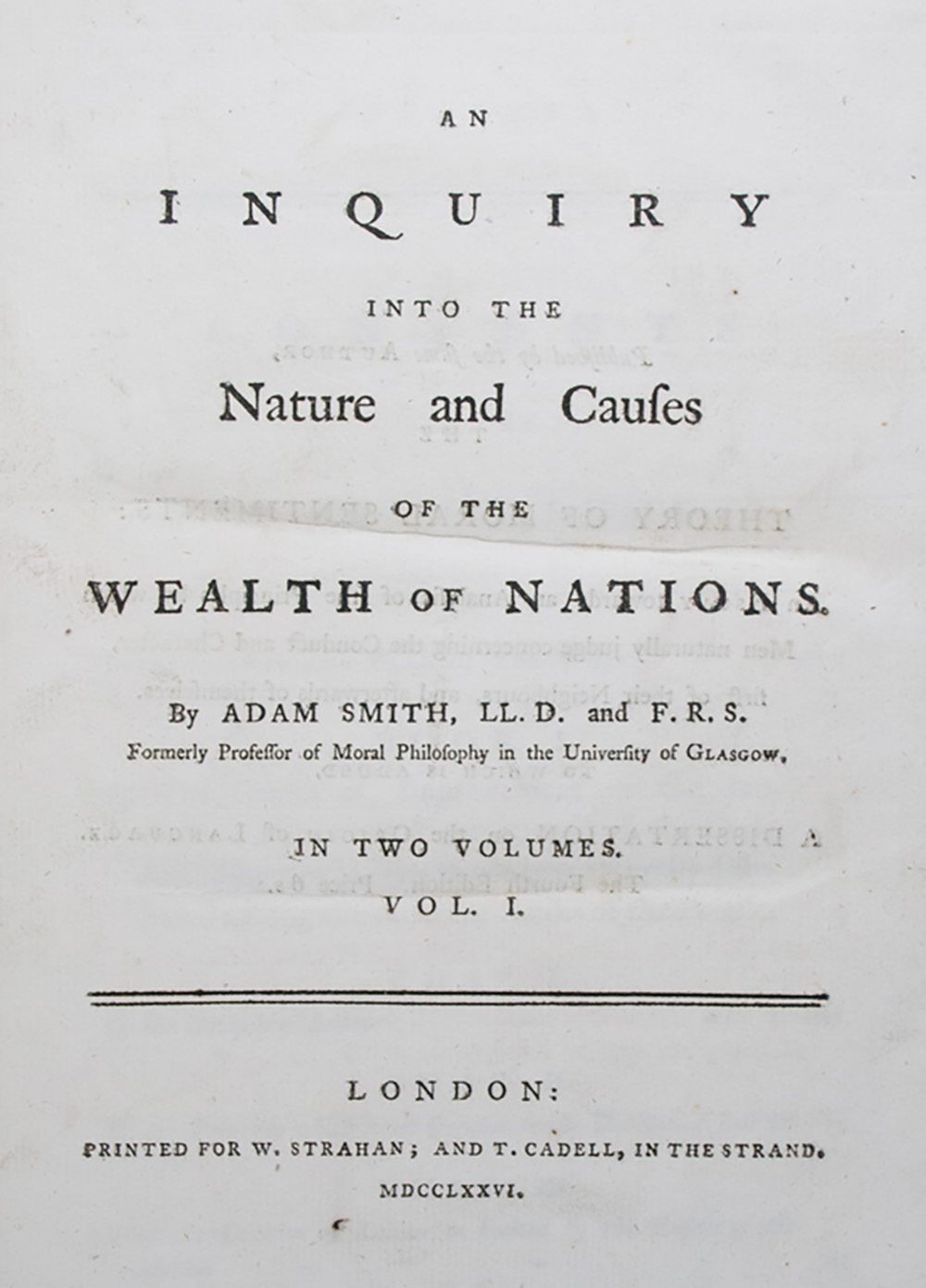

While Hume, Reid and Stewart exemplified the development of abstract philosophical thinking during the Scottish Enlightenment, their contemporary, Adam Smith represented the more practical aspects as a political economist and author of the world famous An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776) which laid the foundations of free market economic theory as we know it today. On the one hand Smith stated that:

“It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.”

But on the other hand, he recognized the dangers of unbridled capitalism:

“No society can surely be flourishing and happy, of which the far greater part of the members are poor and miserable.”

Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, first edition

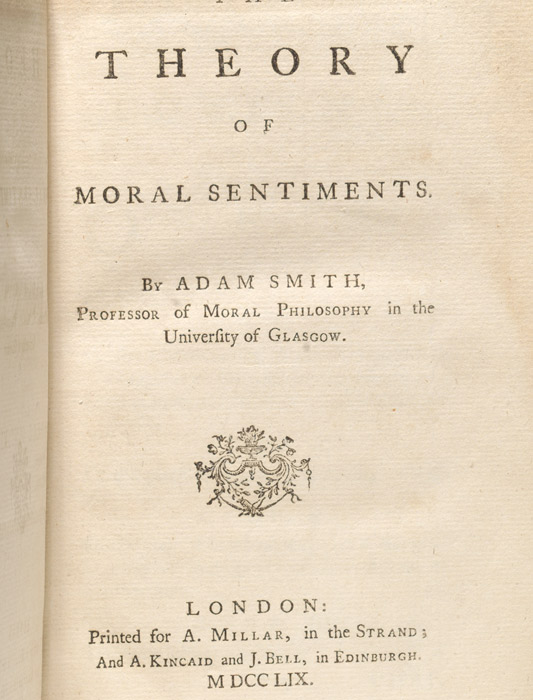

Adam Smith, The Theory of Moral Sentiments

Interestingly, The Wealth of Nations was not Smith’s first major work. In contrast, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, which was published seventeen years before in 1759 sought to explain that mankind’s innate conscience develops through social interaction leading to a "mutual sympathy of sentiments." Some scholars have seen an irreconcilable paradox between these two works. However, others detect a more nuanced understanding of human nature, which can display different aspects depending on the situation, exactly in keeping with the subtlety of the Scottish School of Common-sense.

There were many other practical outcomes of the Edinburgh Enlightenment, some of which you will learn more of during the Old and New Town walks. A few key examples can be mentioned here. In the field of medicine John Rutherford (Professor of the Practice of Medicine 1726–1765 at Edinburgh Medical School) was the champion of the “Edinburgh Method” of clinical teaching, whereby students were educated in the hospital with live patients as opposed to abstract classroom teaching. Building on this, the President of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh from 1773–1775, William Cullen elaborated a system-based approach to the practice of medicine: a previously uncharted level of organization, which became the basis of clinical teaching at the school from the middle of the seventeenth century onwards. Francis Home (1719 – 1813) physician and first Professor of Materia Medica at The University of Edinburgh was the originator of first attempts to vaccinate against measles. Joseph Black, although also a Professor of Medicine at the university of Edinburgh for thirty years beginning in 1766, is best known for his research in chemistry. His theory of latent heat was the cornerstone of the science of thermodynamics, while he also demonstrated that carbon dioxide is produced by animal respiration and microbial fermentation and was the first creator of chemical formulae.

James Hutton (1726–97) came to be viewed as the "Father of Modern Geology" based primarily on his seminal work, Theory of the Earth, in which he wrote of the earth that “We find no vestige of a beginning and no prospect of an end.” As a consequence, and as the reader can imagine, traditional theologians of the day were not enamoured of Hutton.

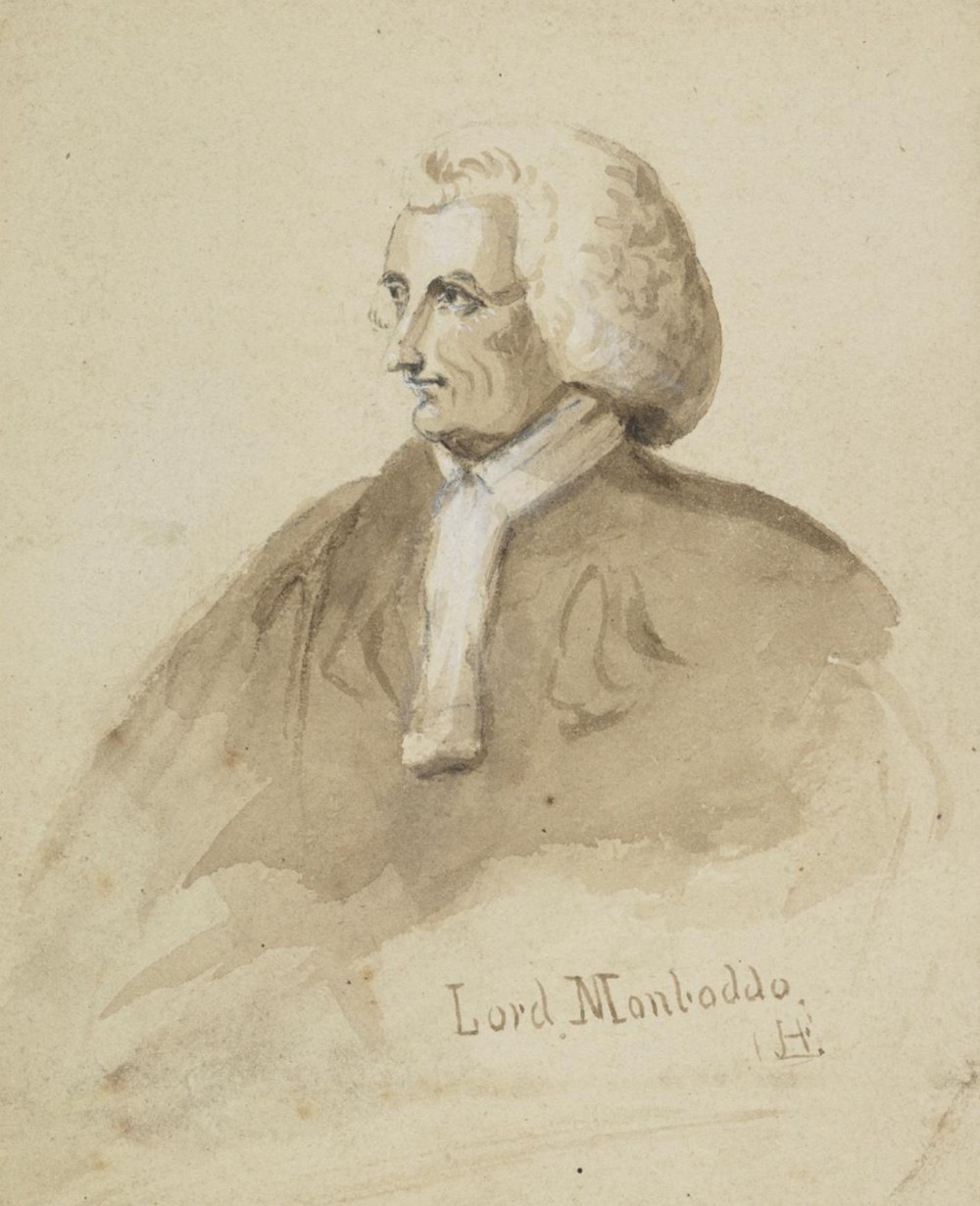

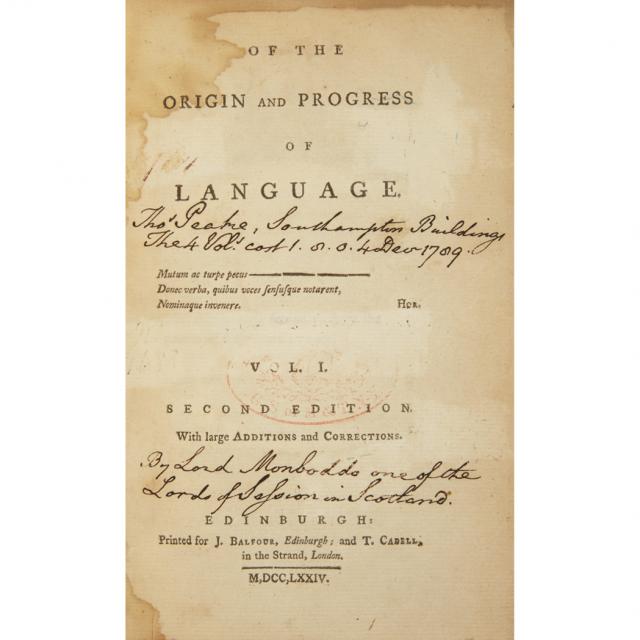

James Burnett, Lord Monboddo (1714–99) is considered the founder of comparative linguistics. In his work entitled The Origin and Progress of Language he provided evidence that language skills evolved in response to changing environments and social structures. But perhaps more striking, on the basis of this evolution, he was also the first to put forward what is currently termed the single-origin hypothesis, or the theory that man originated at a single region of the earth. As a corollary of these various concepts, he also contributed to early concepts about biological evolution, thus anticipating Darwin’s principles of natural selection.

Lord Monboddo, Unknown Artist

Scottish National Gallery

Lord Monboddo, Of the Origin and Progress of Language

Known as "the father of modern sociology" Adam Ferguson (1723 – 1816) eventually became professor of natural philosophy at Edinburgh University in 1759, moving on to the chair of "pneumatics" and moral philosophy in 1764. His most famous work was An Essay on the History of Civil Society published in 1767, which re-established the classical concepts of civic republicanism.

In architecture, the Scottish neo-classicist architect and interior designer, Robert Adam (1728–1792) was a leader of the classical revival in the United Kingdom from 1760 until his death. He influenced Western architecture in Europe and North America, most notably through his renowned Adam Style.

Accompanying these advances in the sciences, there was a flourishing of literary talent and during the Old and New Town walks you will see places of interest associated with Allan Ramsay, James Boswell, Robert Burns, Walter Scott, John Home, Robert Fergusson, Tobias Smollett and James Hogg. You will also view the site of publication of the first Encyclopedia Britannica, edited by William Smellie and proofread by Robert Burns, which appeared in 100 weekly instalments from December 1768 to 1771.

As the enlightenment matured, a formal institution was needed to recognize contributors and promote their achievements. Thus, the Royal Society of Edinburgh, which evolved from the earlier Royal Medical Society and Edinburgh Philosophical Society, was formally established in 1783 by Royal Charter for “the advancement of learning and useful knowledge” in order to embrace a more multidisciplinary approach to considering and solving the key issues of the age. You will see the current premises of the society in George Street during the New Town walk. By the time of its establishment, the elite of Edinburgh had migrated from the squalid and overcrowded Old Town to the spacious cleanliness of the Georgian New Town. This transformation permitted the city to further cement its international reputation as a bastion of enlightened culture. Read further in the following supplementary introduction, entitled The Cultural Geography of Edinburgh, to understand how history conspired with geography to promote the Edinburgh Enlightenment.

The Scottish Enlightenment had influence far beyond Scotland. It made disproportionately large contributions to British science and humanities extending well into the nineteenth century. Although, as mentioned above, the French and Scottish versions of the enlightenment differed in style, there was considerable interchange of ideas between key figures of both countries. Both movements encompassed radical thinking, contributing to revolution in France, while Scotland focussed on democracy, freedom of speech, equal opportunity and education for all. The prominence of education in Scotland was instrumental in the genesis of the enlightenment itself, but also allowed Scots to take leading roles as the British Empire became established, a fact which eventually became somewhat of a thorn in the side for the English.

Possibly the two greatest of the impresarios of the enlightenment were David Hume and Adam Smith. Hume has had a fundamental influence on philosophical thinking throughout history, while Adam Smith laid the foundations of free market economic theory and thus prefigured the prevalence of capitalism today.

But perhaps the greatest impact of the Scottish Enlightenment was to be felt in the United States. A large number of Scots emigrated to America in the eighteenth century. John Witherspoon (1723 – 1794) was a Presbyterian minister who became a President of the College of New Jersey, the forerunner of Princeton University. He introduced transformative educational initiatives, but also championed the ideas of Scottish Common-Sense Realism in America. This thinking together with the enlightenment concepts of other Scottish philosophers such as Francis Hutcheson, Adam Smith, Thomas Reid, Dugald Stewart and David Hume were instrumental in instigating the American Revolution and the development of the United States Constitution. James Wilson (1742 – 1798) was a Scottish educated Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States and one of the Founding Fathers who attended the Constitutional Convention in 1787. He emphasized the Scottish ideal holding judicial supremacy over the legislature and executive, which was incorporated into the Constitution and remains a cornerstone of governance in the United States, despite attempts by some current politicians to undermine the concept.

Famously, Wilson wrote the following: “That men ought to be governed, seems to have been agreed on all hands: the reason is, that, without government, they could never attain any high or permanent share of perfection or happiness. But the question has been ― by whom should they be governed? And this has been made a question, by reason of two others ― by whom can they be governed? ― are they capable of governing themselves?”

The author of this guide was impressed by a student’s paper available online* entitled “The Scottish Enlightenment, the American Revolution and U.S. Constitution,” in which additional Scottish Enlightenment influences on the Constitution are enumerated as follows:

“Other Scottish Enlightenment ideals can be found throughout the Constitution. No Title of Nobility shall be granted by the United States. Rejecting calls for the establishment of an official religion, the Constitution provides: no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States. Emphasizing the importance of the republic of letters and scientific advancement, Congress was given the power to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries. U.S. Const., Art., I, § 8 provided Congress the power to tax, borrow money, coin money, establish standard weights and measures, and to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian tribes. In short, the federal government was given substantial powers to promote the economy just as Smith advocated in the Wealth of Nations."

Our generation owes a considerable debt to the enlightenment, including that of Scotland and of Edinburgh in particular. If we hold fast to the principles of the enlightenment, to its focus on the study of man, on logic and reason and to its promotion of education and evidence-based thinking, we stand a better chance of confronting the wave of ignorance and disdain for the truth which is currently sweeping the world.

*The Scottish Enlightenment, the American Revolution and U.S. Constitution