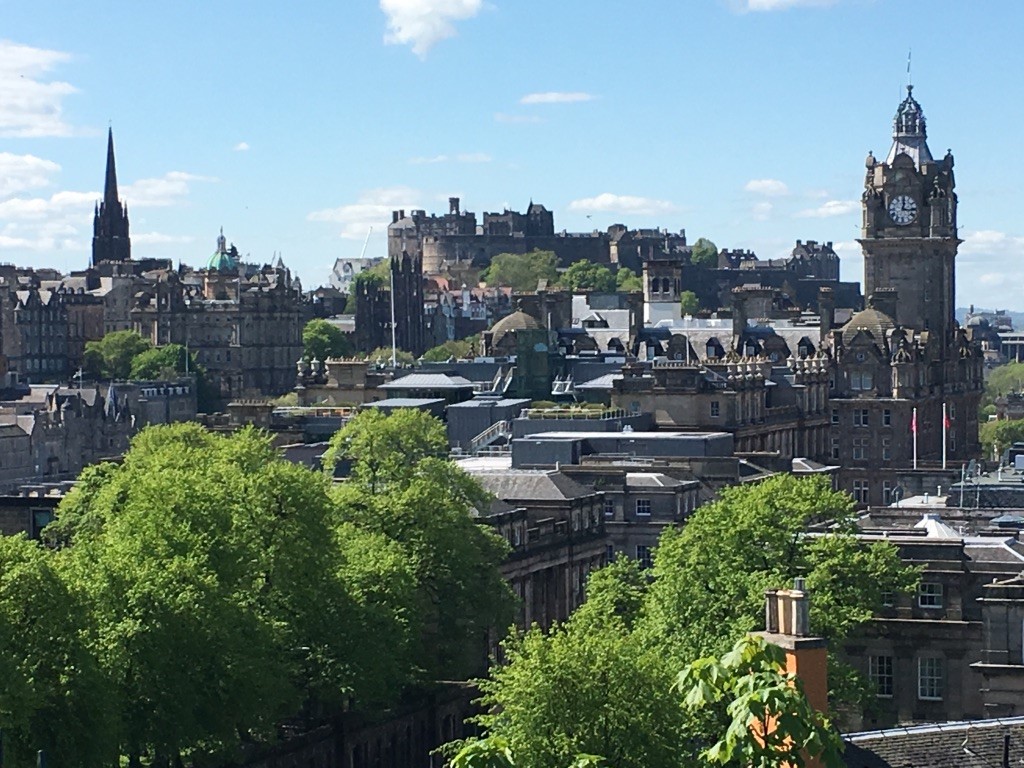

View of Edinburgh from the Castle

By Frederic Bourgeois de Mercey (1803-1860)

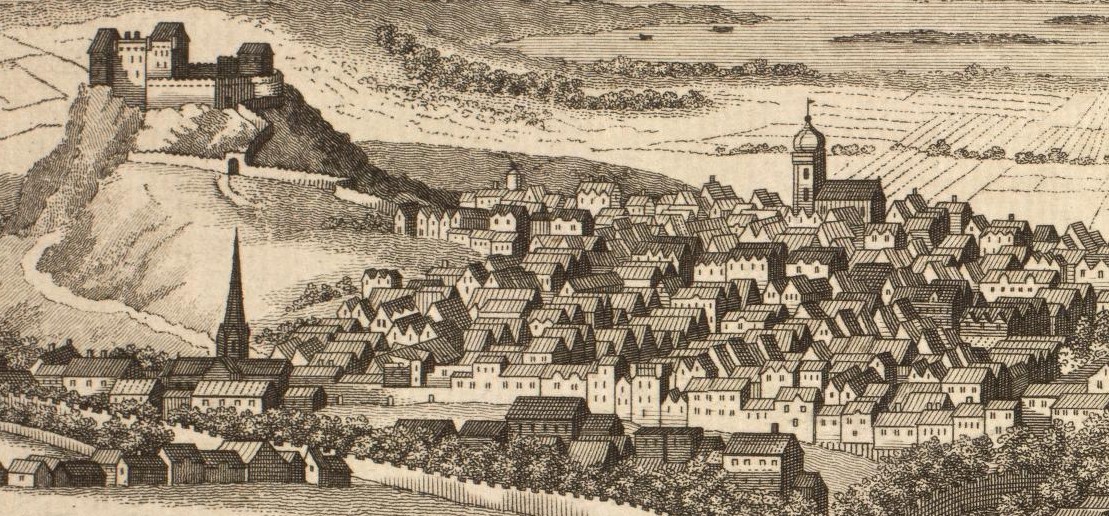

John Speed’s Prospect of Edinburgh, 1610

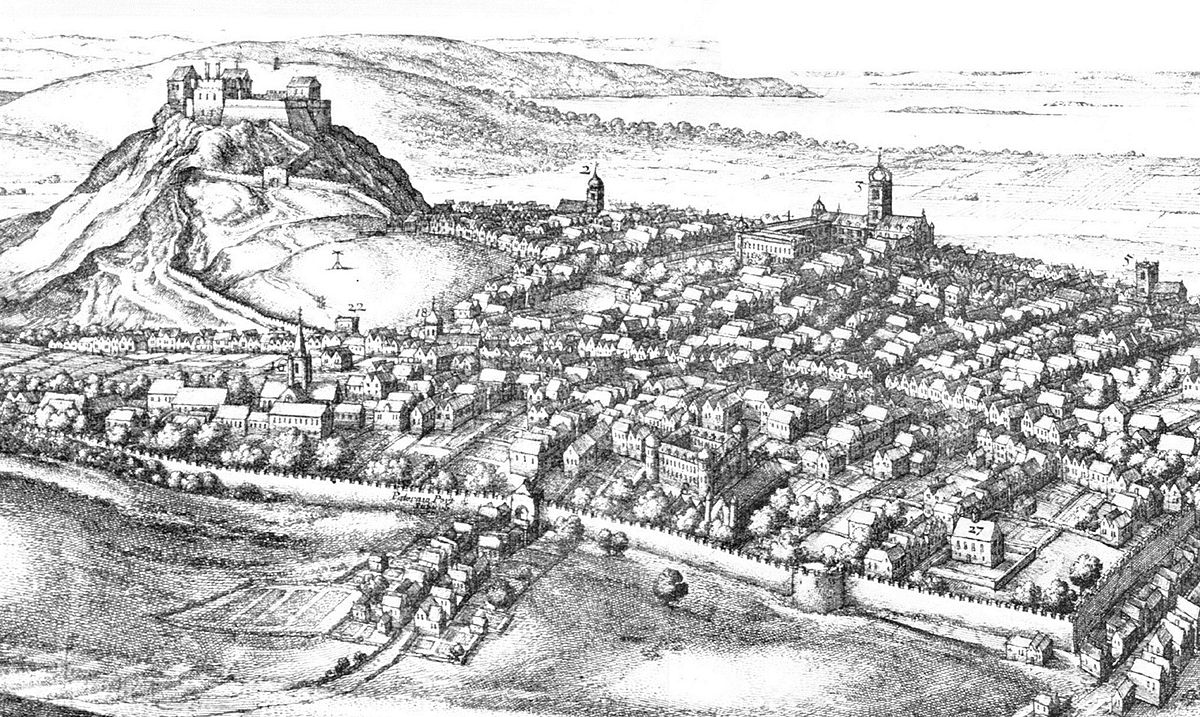

Edinburgh 18th Century, Castle and Old Town

By G H Miller, The New And Universal System of Geography, 1769

The Cultural Geography of Edinburgh

It would be more correct to say, however, that the natural topography has, over the centuries, dictated the development of the city, defined its history and even influenced its culture.

You will begin your Old Town walk at the very origin of the city at its iconic castle, which stands on the summit of an extinct volcano. The site has been occupied since the 2nd. century AD and a castle was built here by David I in the 12th. century. It is a natural location for security. With the rock falling away steeply on three sides, it is a crag, consisting of resistant, hard material, around which a glacier passed. The crag then served, in classic geological fashion, as shelter to softer material in the wake of the glacier, forming a long gently sloping tail to the east. Protection from this east side was provided by a sturdy portcullis and ditch. The Old Town of Edinburgh was built gradually, over centuries, down the tail of the crag along a series of streets, which came to be known as the Royal Mile, beginning with Castle Hill, followed by the High Street, the Lawnmarket, the Canongate and ending at Abbey Strand with Holyrood Palace, the current Queen’s residence in Edinburgh. However, the very topography of this tail eventually imposed daunting physical constraints. In order to expand availability for more housing, alleyways, known locally as closes or wynds, were constructed from the Royal Mile to the north and south in a fishbone pattern. These lead to inner courtyards, where additional construction was possible, still within the confines of the slope. In addition, construction extended upwards, sometimes to ten stories or more, forming the world’s first “skyscrapers” while cellars were excavated downwards below street level. Nowadays the resulting somewhat bizarre, but nonetheless picturesque conglomeration is a renowned tourist attraction and has, together with the later New Town of Edinburgh, been recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site. According to H.G. Graham in his work entitled The Social Life of Scotland in the Eighteenth Century (1906):

“In the flats of the lofty houses in wynds or facing the High Street the populace dwelt, who reached their various lodgings by the steep and narrow 'scale' staircases [stair-towers] which were really upright streets. On the same building lived families of all grades and classes, each in its flat in the same stair—the sweep and caddie in the cellars, poor mechanics in the garrets, while in the intermediate stories might live a noble, a lord of session, a doctor or city minister a dowager countess, or writer; higher up, over their heads, lived shopkeepers, dancing masters or clerks.”

Edinburgh in the 17th Century (detail),

by Wenceslas_Hollar, 1670

Indeed, by the seventeenth century, the overcrowding had reached breaking point with more than 50,000 inhabitants crammed into the city, resulting in unbelievable squalor. In the absence of any system of sewage, waste was thrown unceremoniously from the windows of the tall buildings directly onto the street, accompanied by the infamous cry of “gardyloo” derived from the French “garde à l’eau.” The eventual destination of much of the town’s waste, as well as a dumping site for dead bodies, was the Nor’ Loch at the north base of the castle rock. The stench, along with pollution from coal fires and chimneys, led to the town attaining the unpleasant sobriquet "Auld Reekie." The general insalubrious character of the city was further exacerbated by an epidemic of alcoholism, severely limiting life expectancy and often leading to blindness because of the methanol contamination of poorly distilled spirits.

And yet, the Edinburgh Enlightenment was born among these miserable circumstances. The paradoxically high level of education of the populace, perhaps together with the proximity of living quarters for the poor and wealthy, seemingly spurred the elite into action. The cultural revival that had begun in the 1740’s was already in full swing by 1751, when one night in September a six-storey tenement on the Royal Mile collapsed unexpectedly. This was not the first such occasion, but this time, individuals from some of Scotland’s most prestigious families were among the dead. A prominent member of the city’s elite, counted among the initiators of the Enlightenment, was the Lord Provost, George Drummond (1688–1766), who now devoted the rest of his life to enhancing the city. During your walks in the Old and New Towns you will hear more about Drummond, one of the founders of the Select Society which played a key role in developing Enlightenment thinking. It had long been his ambition to expand the city to the North. Therefore, in 1752 he established the Commission of Proposals for Public Works, with the aim to “improve and enlarge the city and to adorn it with public buildings which may be for the national benefit.” He justified the commercial value of his vision with the following wording:

“Wealth is only to be obtained by trade and commerce, and these are only carried on to advantage in populous cities. There also we find the chief objects of pleasure and ambition, and there consequently all those will flock whose circumstances can afford it.”

In 1752, Lord Gilbert Elliot Minto authored the Proposals for Carrying on Certain Public Works in the City of Edinburgh. It took a further ten years to accumulate funding for the ambitious enterprise. It was recognized that a bridge over the Nor’ Loch would be necessary to connect the Old Town with the proposed New Town. The loch itself was drained and the North Bridge constructed in 1763. In the same year a competition for the design of the New Town was launched by George Drummond and won by James Craig (1739 – 1795) who was aged only 21 at the time.

James Craig, by David Allan

London, National Gallery

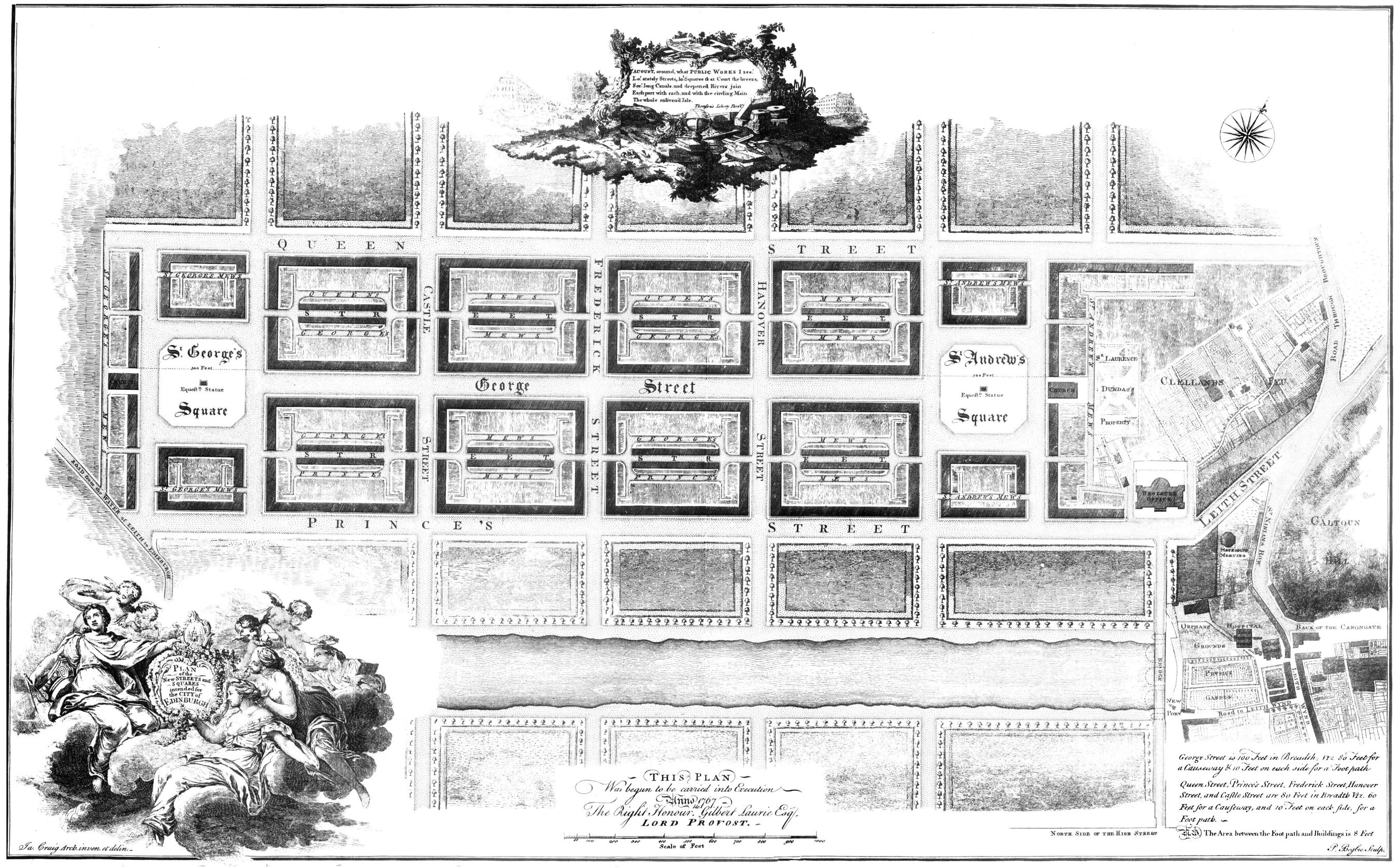

After some revisions by an appointed committee, the final version as illustrated below, consisted of a simple grid design with three parallel, main streets, Princes Street, George Street and Queen Street, bound by squares at each end, now named St. Andrews Square and Charlotte Square. In keeping with Scotland’s new role, after the Act of Union in 1707, as “North Britain,” the street names were those of members of the Hanoverian royal family and the eventual design of the residences have come to be known as the Georgian style. These streets and squares will be the main thoroughfares of your New Town walk.

The result was a masterpiece of urban planning, mostly finished by 1820, with the completion of Charlotte Square, built to a design by Robert Adam, and a remarkably uniform example of the architecture in its own right. The contrast with the Old Town even today is stunning. The city’s elite, including many of the impresarios of the Enlightenment soon decamped from the squalid Old Town and took up residence in the spacious and elegant mansions of the New Town, albeit at considerable expense. Close to the start of your New Town walk, you will view and have the opportunity to visit a museum called the Georgian House at number 7 Charlotte Square, which was bought in 1796 by John Lamont of Lamont, 18th Chief of the Clan Lamont for £1,800. He was extravagant, furnishing the house lavishly, employing many servants and indulging in expensive entertainment as was expected during that era. Nonetheless, the museum will provide you with an excellent idea of how such a family lived in those days.

Map of the first plan of Edinburgh New Town by James Craig, 1768

Wikimedia Commons

It was in this New Town that the Edinburgh Enlightenment reached its zenith and the city cemented its international reputation, somewhat expressly furthered by the conscious efforts of the elite who adopted the sobriquet "Athens of the North." On Princes Street you will see the Royal Scottish Academy, built by William Henry Playfair in 1822-6. Together with the adjacent National Gallery of Scotland immediately behind, their Greek inspired designs contributed to Edinburgh’s image as the new Athens of the North. To some extent this name also reflected the similar topography of the two cities, both of which boast spectacular structures on impressive hills in their city centres. At the east end of Princes Street you will come across a collection of monuments on Calton Hill, including the National Monument, the Playfair Monument, the Royal Observatory and the Royal High School, all based on Greek designs. From that hill there is a spectacular view of both the Old and New Towns, which crystallizes the theatrical nature of the city’s topography and architecture. The author surmises that as you walk in the two towns of Edinburgh you will have little difficulty in imagining the history, cultural vibrancy and unique personalities that consituted the Edinburgh Enlightenment.

View of Edinburgh from the Calton Hill (author’s own photograph)